Chapter 8Nonsquare matrices as transformations between dimensions

"On this quiz, I asked you to find the determinant of a 2x3 matrix. Some of you, to my great amusement, actually tried to do this.”

- Linear algebra professor

In discussing linear transformations so far, we've only really talked about transformations from 2d vectors to other 2d vectors, represented with 2x2 matrices, or from 3d vectors to other 3d vectors, represented with 3x3 matrices. By now in the series you actually have most of the background you need to start pondering a question like this on your own, but we'll start talking through it just to give a little mental momentum.

2d to 3d

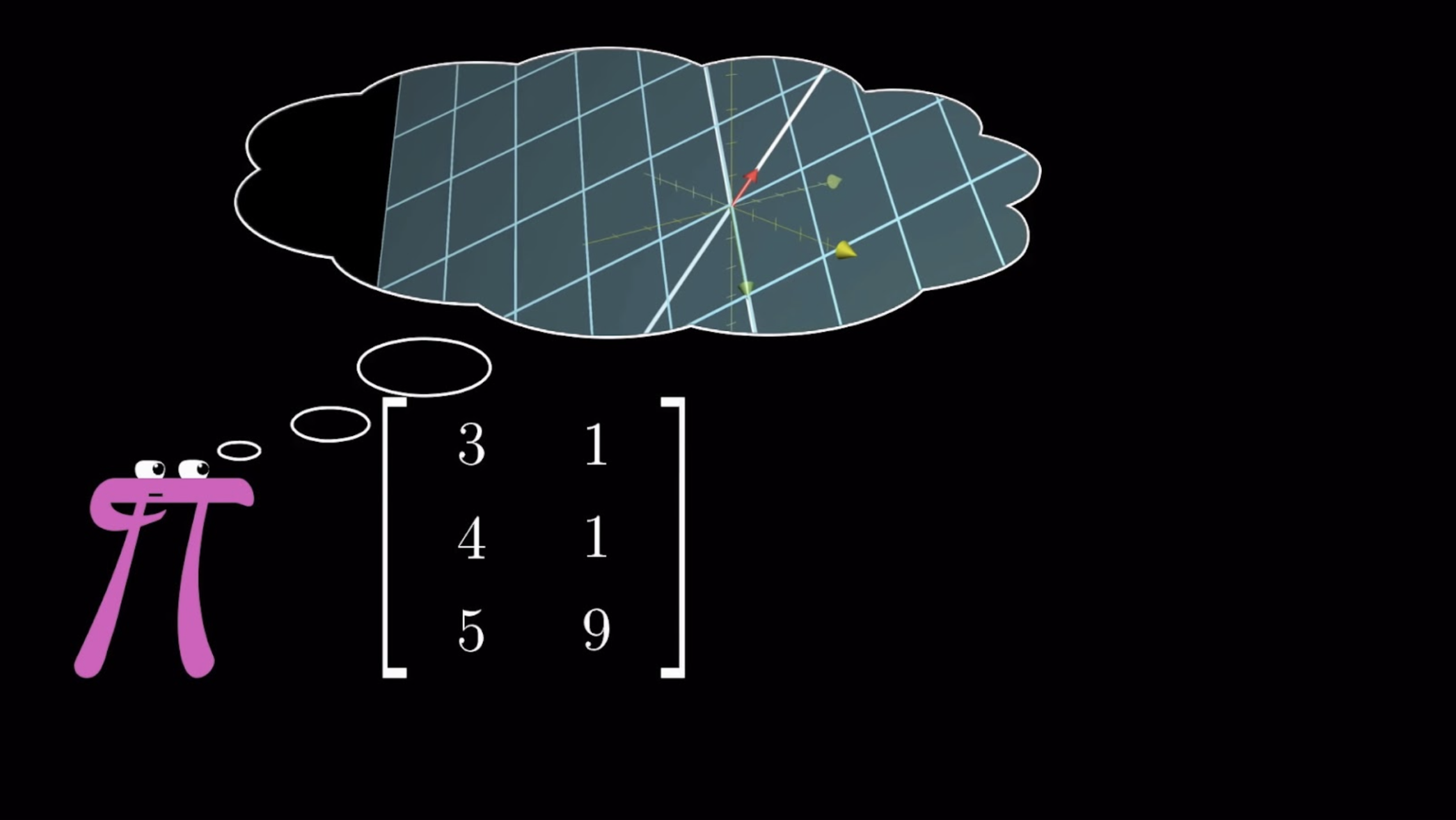

It's perfectly reasonable to talk about transformations between dimensions, such as a transformation from 2d space to 3d space. Again, what makes one of these linear is that grid lines remain parallel and evenly spaced, and the origin maps to the origin.

What we have pictured here is the input space on the left, which is 2d space, and the output of the transformation shown on the right. The reason we're not showing the inputs move to their outputs like we usually do is not just visualization laziness, it's worth emphasizing that 2d vector inputs are a very different animal from the 3d vector outputs, living in a completely separate and unconnected space.

Encoding such a transformation with a matrix is really just the same thing as what we've done before: Look at where each basis vector lands, and write the coordinates of its landing spot as the columns of a matrix.

For example, look at the matrix that corresponds to the current transformation that takes to the coordinates , and to the coordinates . The first column represents where lands and the second column represents where lands.

Notice, this means the matrix encoding our transformation has three rows and two columns, which, to use standard terminology, makes it a "3x2 matrix".

To use the language of the last chapter, the column space of this matrix, the place where all vectors land, is a 2d plane slicing through the origin of 3d space. But the matrix is still full-rank, since the number of dimensions in this column space is the same as the number of dimensions in your input space.

So if you see a 3x2 matrix out in the wild, you can know that it has the geometric interpretation of mapping 2 dimensions to 3, since the two columns indicate that the input space has 2 basis vectors, and the 3 rows indicate that the landing spot for each basis vector is described with 3 coordinates.

Likewise, if you see a 2x3 matrix, with 2 rows and 3 columns, what do you think that means?

Well, the 3 columns indicate that the starting space has 3 basis vectors, so we're starting in 3 dimensions. And the 2 rows indicate that the landing spot for each of those 3 basis vectors is described with only 2 coordinates, so they must be landing in 2 dimensions.

This means it's a transformation from three-dimensions down to two; a transformation that would feel deeply uncomfortable to experience.

2d to 1d

You could also have a transformation from two dimensions to one dimension. One-dimensional space is really just the number line, so a transformation like this takes in 2d vectors, and spits out numbers.

Thinking about grid lines remaining parallel and evenly spaced is a bit messy due to all of the squishification, so in this case, the visual understanding for what makes a linear transformation distinct from non-linear transformations is that a line of evenly spaced dots would remain evenly spaced once they're mapped onto the number line.

One of these transformations is encoded with a 1x2 matrix, each of whose 2 columns just has a single entry, indicating the number the lands on and the number that lands on.

This is actually a surprisingly meaningful type of transformation, with close ties to the dot product that we'll talk about next chapter. Until then, we encourage you to play around with this idea on your own, contemplating the meaning of things like matrix multiplication and linear systems of equations in the context of transformations between dimensions.