Chapter 2Linear combinations, span, and basis vectors

"Mathematics requires a small dose, not of genius, but of an imaginative freedom which, in a larger dose, would be insanity."

- Angus K. Rodgers

In the last chapter, along with the ideas of vector addition and scalar multiplication, we described vector coordinates, where there's this back-and-forth between pairs of numbers and two-dimensional vectors.

Now it's possible that vector coordinates were already familiar to many of you, but there's another interesting way to think about these coordinates, which is central to linear algebra. When you have a pair of numbers meant to describe a vector, like , think of each coordinate as a scalar, meaning think about how each one stretches or squishes vectors.

In the -coordinate system, there are two special vectors. The one pointing to the right with length , commonly called "i hat" or "the unit vector in the -direction". The other one is pointing straight up with length , commonly called "j hat" or "the unit vector in the -direction".

Now, think of the -coordinate as a scalar that scales , stretching it by a factor of , and the -coordinate as a scalar that scales , flipping it and stretching it by a factor of . In this sense, the vector that these coordinates describe is the sum of two scaled vectors.

This idea of adding together two scaled vectors is a surprisingly important concept. Those two vectors and have a special name: Together they are called the "basis" of the coordinate system. What this means is that when you think about coordinates as scalars, the basis vectors are what those scalars actually scale.

There's also a more technical definition of basis, but we'll get to that later. Framing our familiar coordinate system in terms of these two special basis vectors raises an interesting and subtle point: We could choose a different pair of basis vectors and get a perfectly reasonable new coordinate system.

Choosing Different Basis Vectors

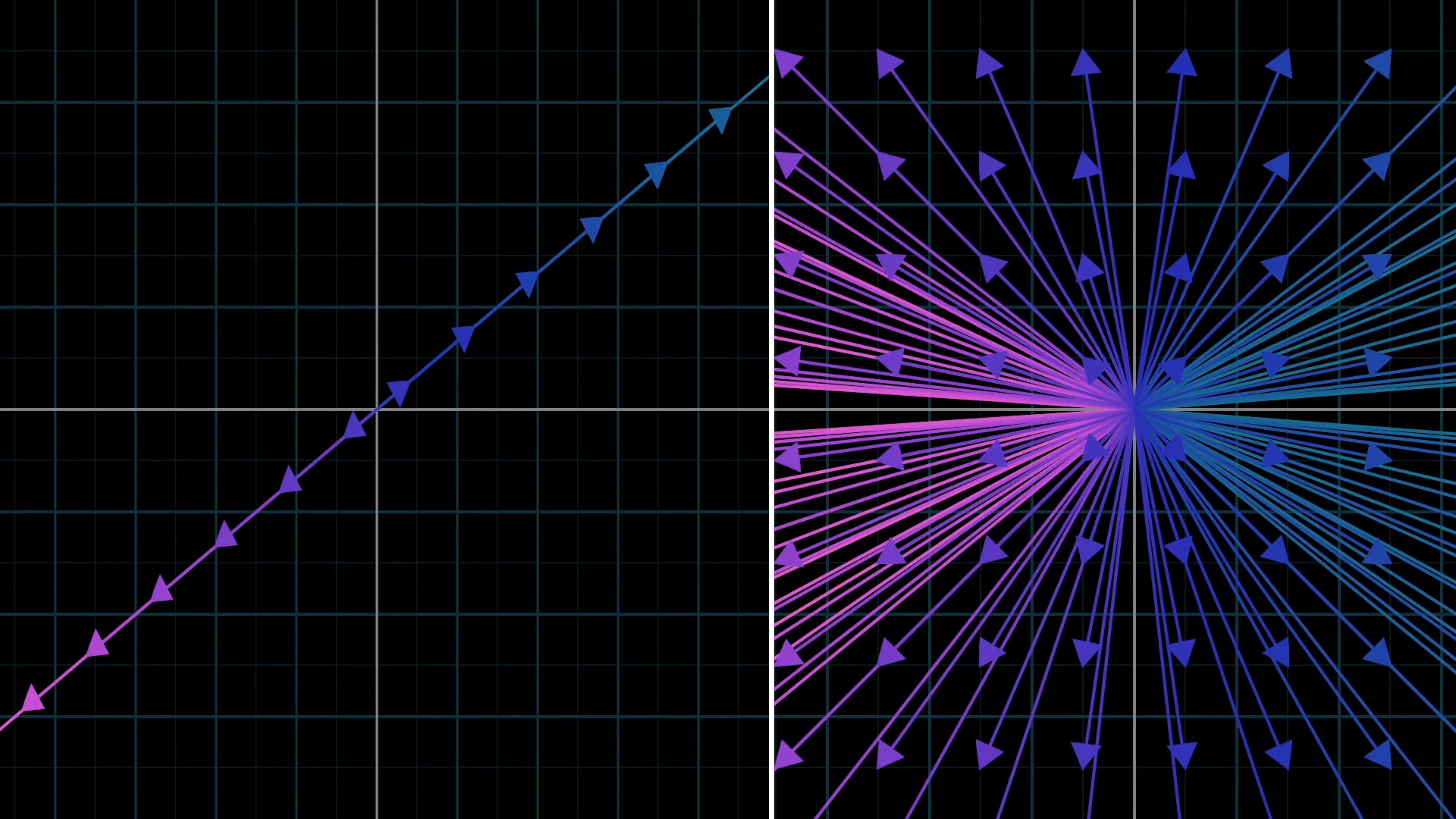

For example, take some vector pointing up and to the right, along with a vector pointing down and to the right.

Take a moment to think about all the different vectors you can get by choosing two scalars, using each to scale one of the vectors, then adding them. Which two-dimensional vectors can you reach by altering your choice of scalars?

The answer is, for these two vectors, you can describe every possible two-dimensional vector this way, and it's a good puzzle to contemplate why. A new pair of basis vectors like this still gives you a way to go back and forth between pairs of numbers and two-dimensional vectors, but the association is definitely different from the version you get using the standard basis of and .

We'll go into much more detail on this point in a later chapter, describing the relationship between different coordinate systems, but for now we just want you to appreciate that any way to describe vectors numerically depends on your choice of basis vectors.

Linear Combinations

Any time you're scaling two vectors and adding them like this, it's called a "linear combination" of those two vectors.

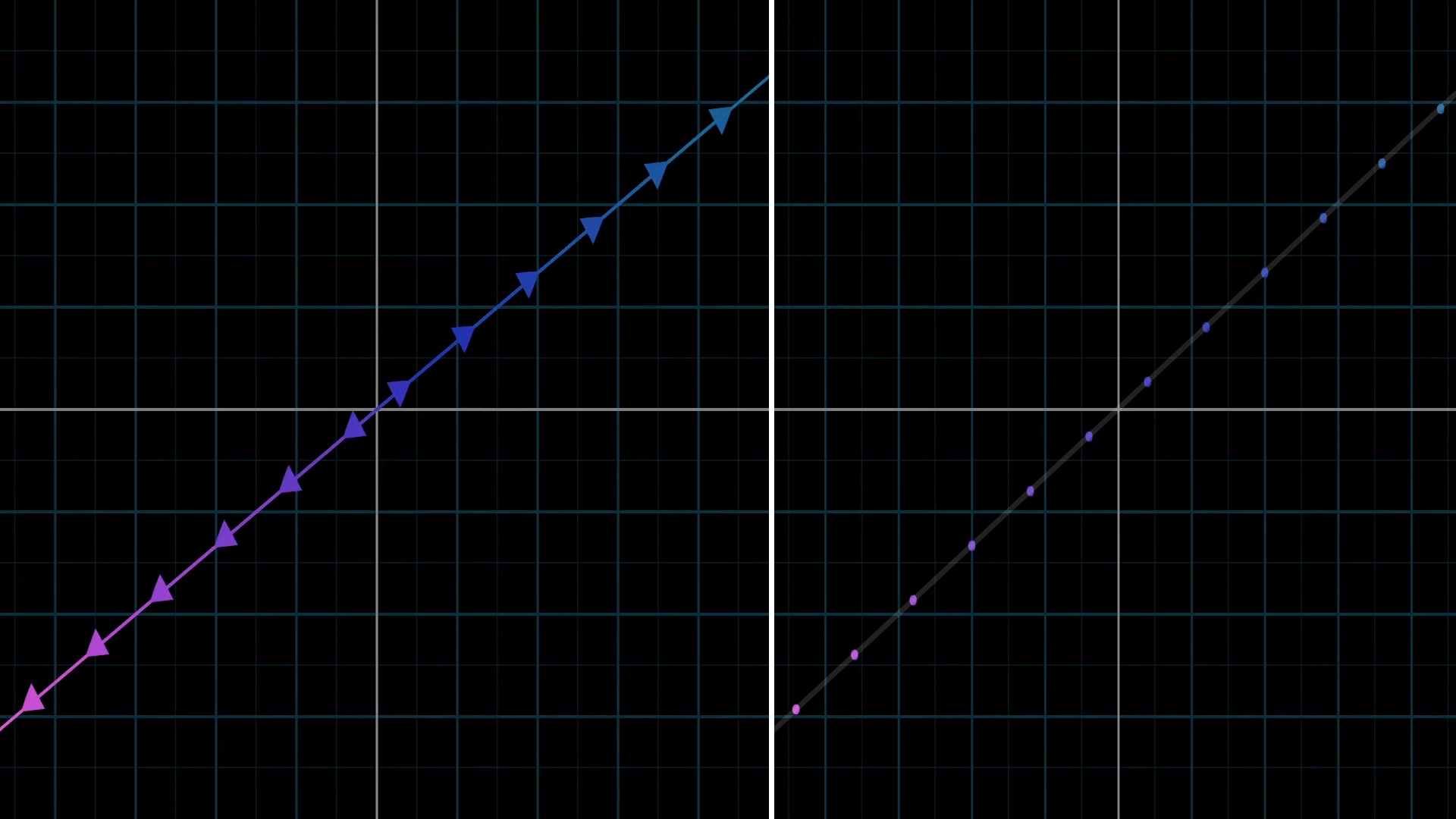

Where does the word "linear" come from here? What does this have to do with lines? Well, when you multiply a scalar by a vector, it changes the magnitude of that vector. Multiplying every real number by the vector produces an infinite line that passes through the origin and the point defined by the vector.

So a linear combination of two vectors is a method of combining these two lines. For most pairs of vectors, if you let both scalars range freely and consider every possible vector you could get, you will be able to reach every possible point on the plane. Every two-dimensional vector is within your grasp.

However, if your two original vectors happen to line up, the lines produced by the scalar multiplication will be the same line, so adding them together can't yield a vector outside of that line.

There's a third possibility too: Both your vectors could be the vector, in which case you'll just be stuck at the origin.

Span

The set of all possible vectors you can reach with linear combinations of a given pair of vectors is called the "span" of those two vectors. Restating what we just saw in this lingo, the span of most pairs of 2D vectors is all vectors in 2D space, but when they line up, their span is all vectors whose tip sit on a certain line.

Remember how we said linear algebra revolves around vector addition and scalar multiplication? The span of two vectors is basically a way of asking what are all the possible vectors you can reach using these two by only using those fundamental operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication.

What two vectors that make up the linear combination will only produce vectors that lie on a single line?

What is the span of and ?

Vectors vs Points

This is a good time to talk about how people commonly think about vectors as points. It gets very crowded to think about a whole collection of vectors sitting on a line, and more crowded still to think about all two-dimensional vectors all at once, filling up the plane.

So when dealing with collections of vectors like this, it's common to represent each one just with a point in space, the point at the tip of this vector. That way, if you want to think about every possible vector whose tip sits on a certain line, just think about that line itself.

Likewise, to think about all possible two-dimensional vectors, conceptualize each one as the point where its tip sits. Then to think about all of them all at once, you can just think about the infinite flat sheet that is two-dimensional space, leaving the arrows out of it.

In general, if you're thinking of a vector on its own, think of it as an arrow, and if you're thinking of a collection, it's convenient to think of them as points.

Span in 3D

The idea of span gets more interesting if we start thinking about vectors in three-dimensional space. For example, if you take two vectors in three-dimensional space that are not pointing in the same direction, what does it mean to take their span?

Well, their span is the collection of all possible linear combinations of those two vectors, meaning all possible vectors you get by scaling each of the two you start with in some way, then adding them together.

You can imagine turning two knobs to change the two scalars defining the linear combination, adding the scaled vectors and following the tip of the resulting vector. That tip traces out some kind of flat sheet cutting through the origin of three-dimensional space.

This flat sheet is the span of the two vectors. Or more precisely, the set of all possible vectors whose tips sit on this flat sheet is the span of your two vectors. Isn't that a beautiful mental image?

What happens if you add on a third vector, and consider the span of all three vectors? A linear combination of three vectors is defined pretty much the same way as for two: Choose three scalars, use them to scale each of your vectors, then add them all together. And again, the span of these vectors is the set of all possible linear combinations.

The linear combination of , , and :

Two things can happen when we add a third vector:

If your third vector happens to be sitting on the span of the first two, then the span doesn't change, you're sort of trapped on that same flat sheet. In other words, adding a scaled version of the third vector to linear combinations of the first two doesn't give you access to any new vectors.

If you just randomly choose a third vector, it's almost certainly not sitting on the span of the first. Since it's then pointing in a separate direction, it unlocks access to every possible three-dimensional vector! The way to think about this is that as you scale the new third vector, it moves around the span of the first two to sweep it through all of space.

It's kind of like you're making full use of the three freely-changing scalars that you have at your disposal to access the full three dimensions of space.

In the case where the third vector was sitting on the span of the first two, or the case where two vectors happen to line up, we want some terminology to describe the fact that at least one of these vectors is redundant, not adding anything to our span. Whenever this happens, where you have multiple vectors, and you could remove one without reducing their span, the relevant terminology is to say they are “linearly dependent”.

Another way of phrasing this would be to say that one of the vectors can be expressed as a linear combination of the others. That is, it's already in the span of the other two.

On the other hand, if each vector really does add another dimension to the span, they are said to be “linearly independent”.

In the next chapter we'll get into matrices and transforming space. See you there!

Questions

Given the span of two vectors and illustrated below:

Which of the following vectors is linearly dependent of the vectors and ?

The technical definition for the “basis” of a space is a set of linearly independent vectors that span that space. Given how we described a basis earlier, and given your understanding of the words “span” and “linearly independent”, why does this definition make sense?

Earlier we learned that any pair of vectors could form a new basis as long as they are linearly independent, meaning that their linear combination can span the entire 2D plane.

If instead, the two vectors are linearly dependent, then they lay on the same line as eachother and their linear combination only yields vectors which lay on the same line.

Given the linear combination of the two vectors illustrated below:

What are the two scalar values for and which form the vector ?