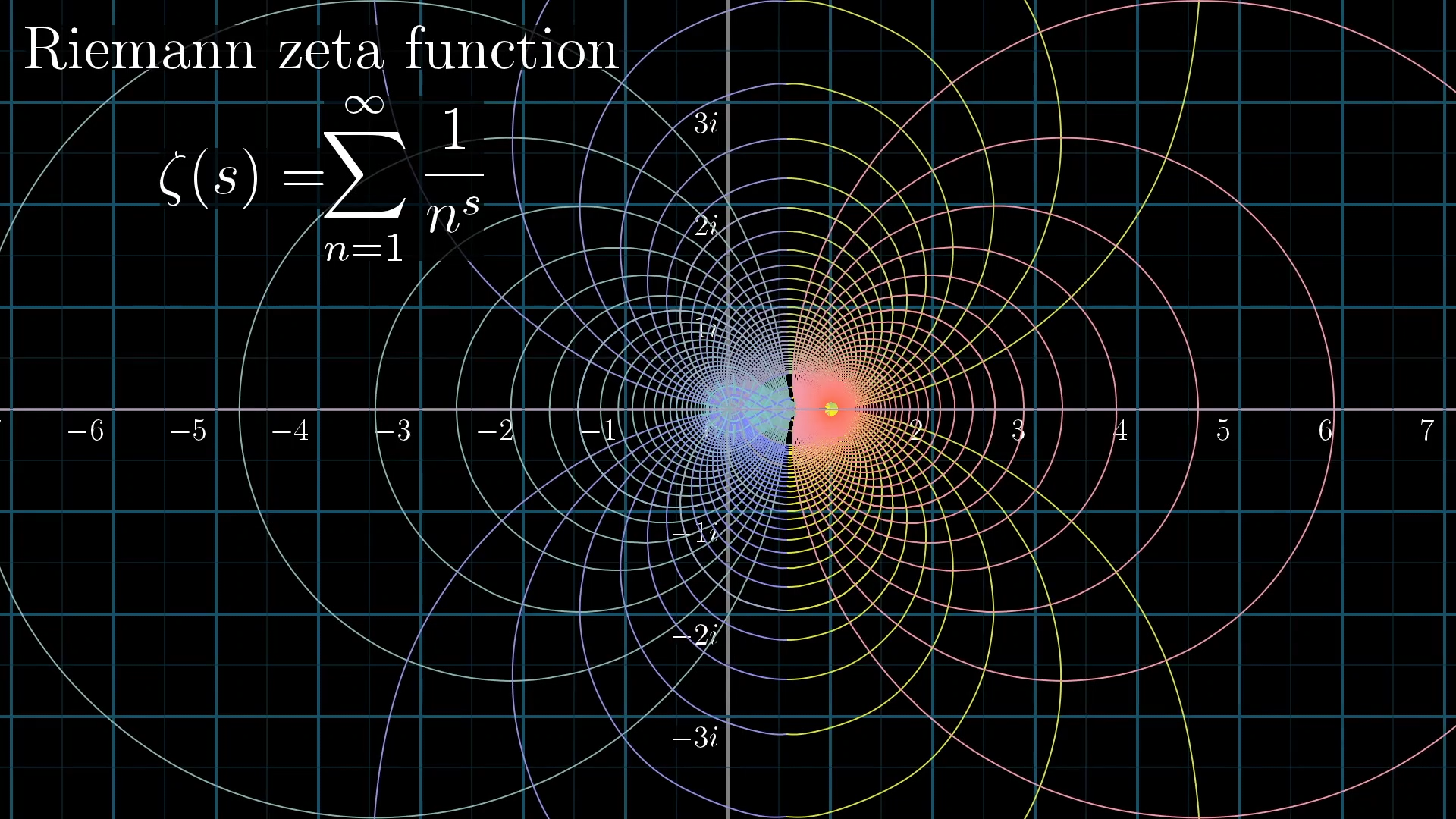

Visualizing the Riemann zeta function and analytic continuation

Introduction

The Riemann zeta function is one of the most important objects in modern math, and yet simply explaining what it is can be surprisingly tricky. The goal of this lesson is to do just that.

Don’t worry, I’ll explain that animation you just saw further below. A lot of people know about this function because there’s a million dollar prize out for anyone who can figure out when it equals 0, an open problem known as the “Riemann hypothesis”.

Some of you may have heard of it in the context of the following divergent sum:

This expression might seem nonsensical, if not obviously wrong. Indeed, the symbol "" is being used a bit loosely in this expression, but there is a true fact which it is trying to express which has everything to do with the zeta function.

However, as any casual math enthusiast who’s searched "Riemann zeta function" knows, its definition references a certain idea known as “analytic continuation”. This is a topic concerning complex functions, and can be frustratingly opaque and unintuitive. What I’d like to do here is explain what this idea of analytic continuation is in a visual and intuitive way, in the service of showing very concretely what the zeta function looks like.

I’m assuming you know about complex numbers, and that you're comfortable working with them. And I’m tempted to say you should know calculus, since analytic continuation is all about derivatives, but for the way I plan to present things I think you might be okay without that.

Define zeta function for real s > 1

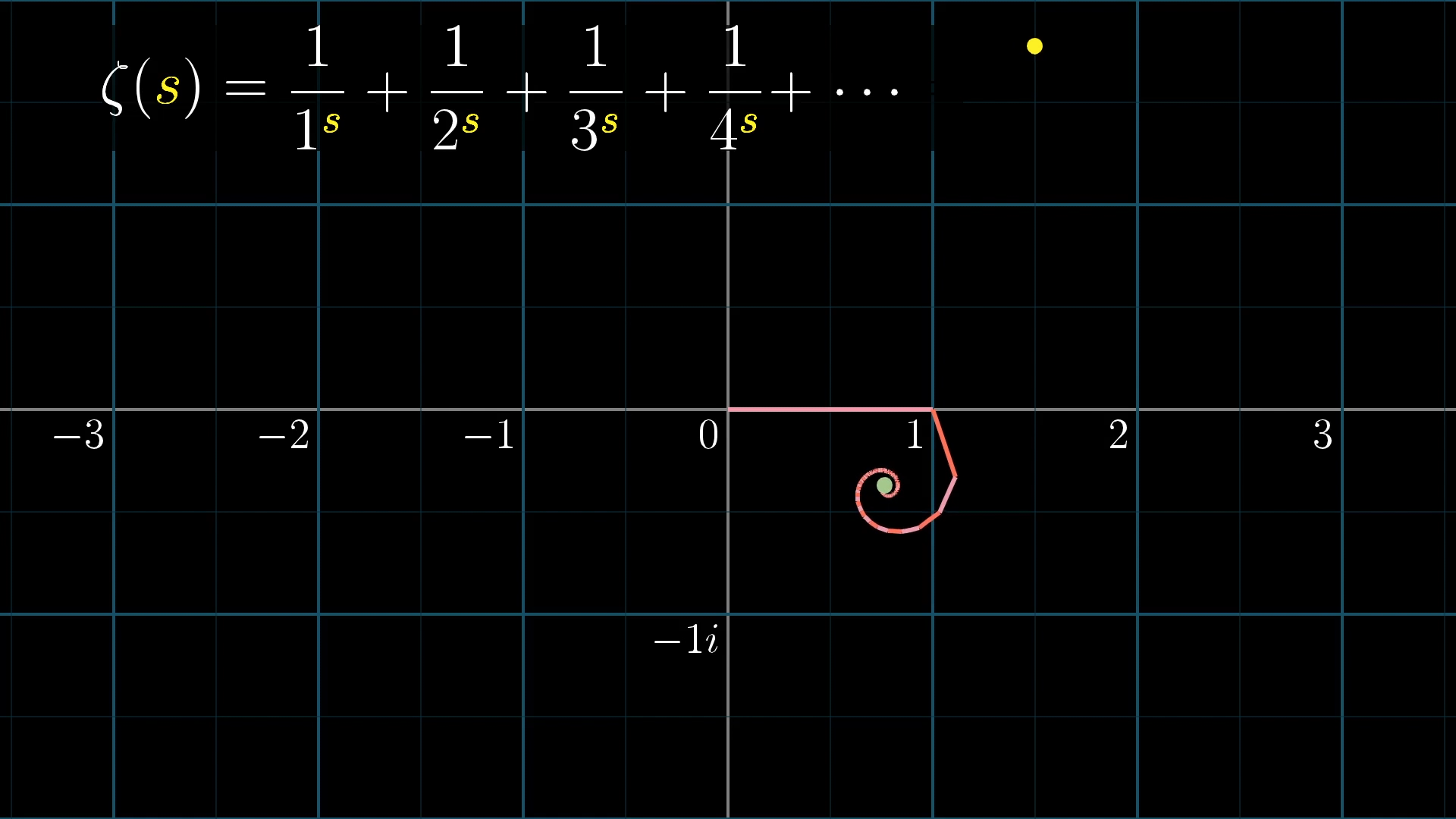

First, let’s define what this zeta function is. For a given input s, the zeta function is a sum of for all natural numbers .

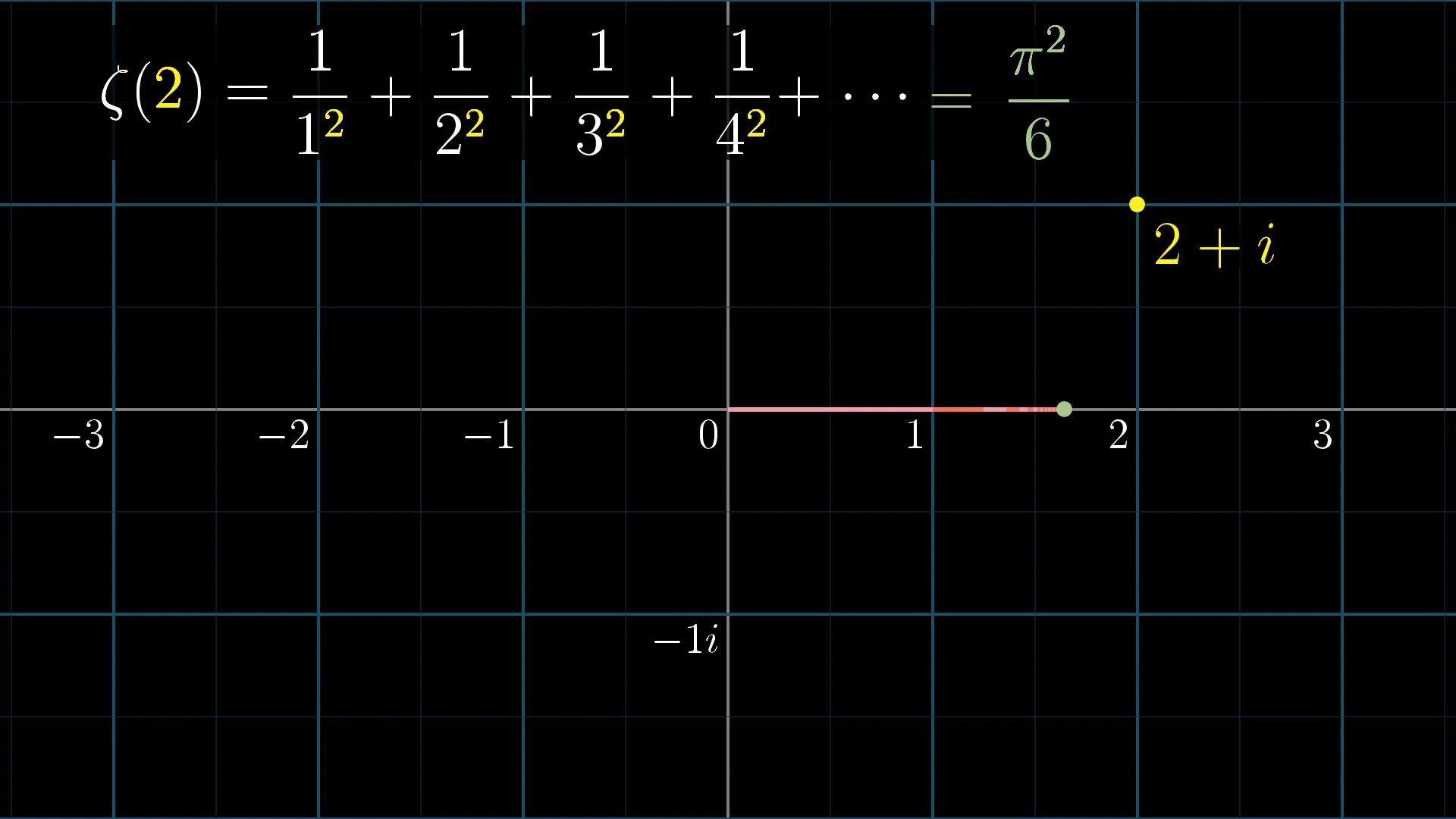

For example, when you plug in s=2, you get

Delightfully, this particular sum converges to .

There’s a nice reason for showing up here, covered in another lesson, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg for why this function is beautiful. You can plug in other values, like 3 or 4 and get some interesting values, and so far it feels pretty reasonable: You’re adding up smaller and smaller amounts, and these sums approach some number.

Which of the following equals ?

Yet, if you read about it, you might see people say . But looking at this infinite sum, that makes no sense.

By raising each term to , you get which obviously doesn’t approach anything, certainly not , right?

And as any mercenary looking into the Riemann hypothesis knows, this function is said to have “trivial” zeros at negative even numbers. For example, this would mean . But plugging in gives you , which also doesn’t approach anything, much less 0. Right?

We’ll get to negative values in a few minutes, but right now let’s just say the only thing that seems reasonable: This function only makes sense when s > 1 , which is when this sum converges. So far, it’s simply not defined for other values.

Extend to complex inputs with Re(s) > 1

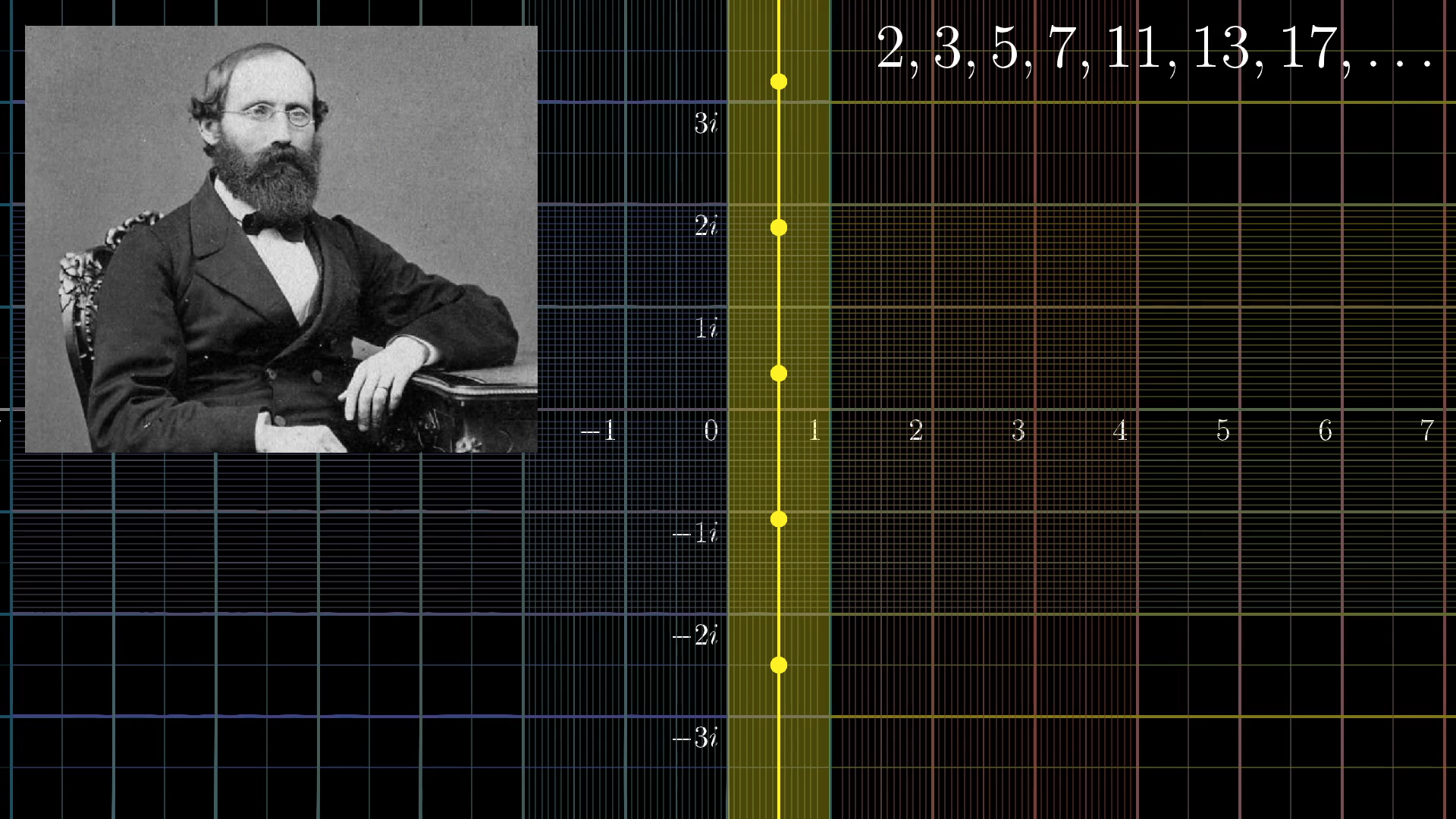

Bernhard Riemann, the mathematician whose name is forever tied to this deceptively simple infinite sum, was a father to complex analysis. This is the study of functions that have complex numbers as inputs and outputs. More specifically, complex functions with which you can do calculus, but more on that in just a bit.

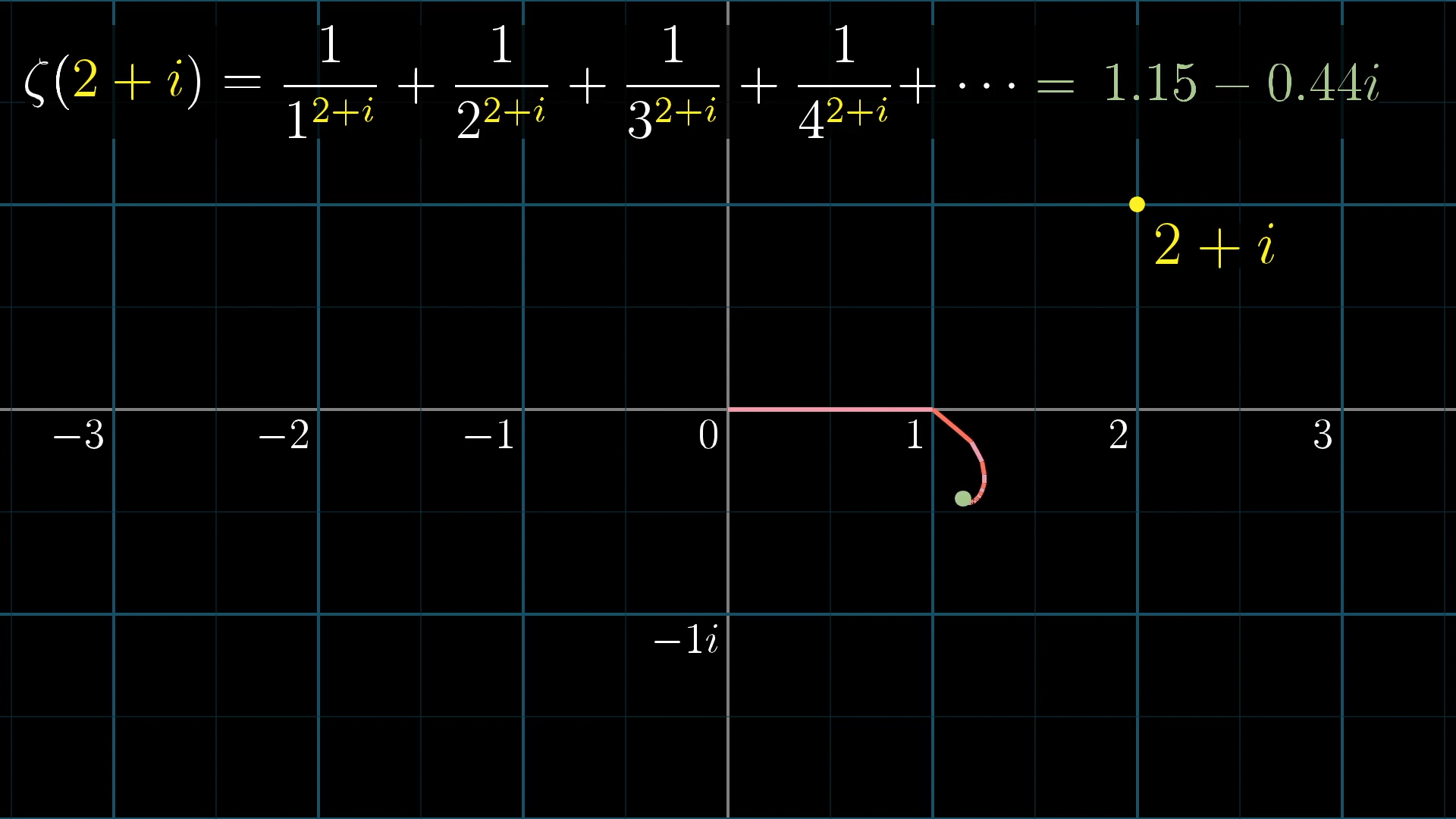

So rather than just thinking about how this sum takes a number on the real number line to another number on the real number line, Riemann asked what happens when you plug in a complex number for s. For example, maybe instead of plugging in to this function, you plug in .

If you’ve never seen the idea of raising a number to the power of a complex value, it can feel kind of strange at first, because it no longer has anything to do with repeated multiplication. But there’s a very natural way to extend the definition of exponents beyond their familiar territory of real numbers, into the realm of complex values.

The basic idea is that when you write something like to the power of a complex number, you can split it up as to the real part, times to the pure imaginary part.

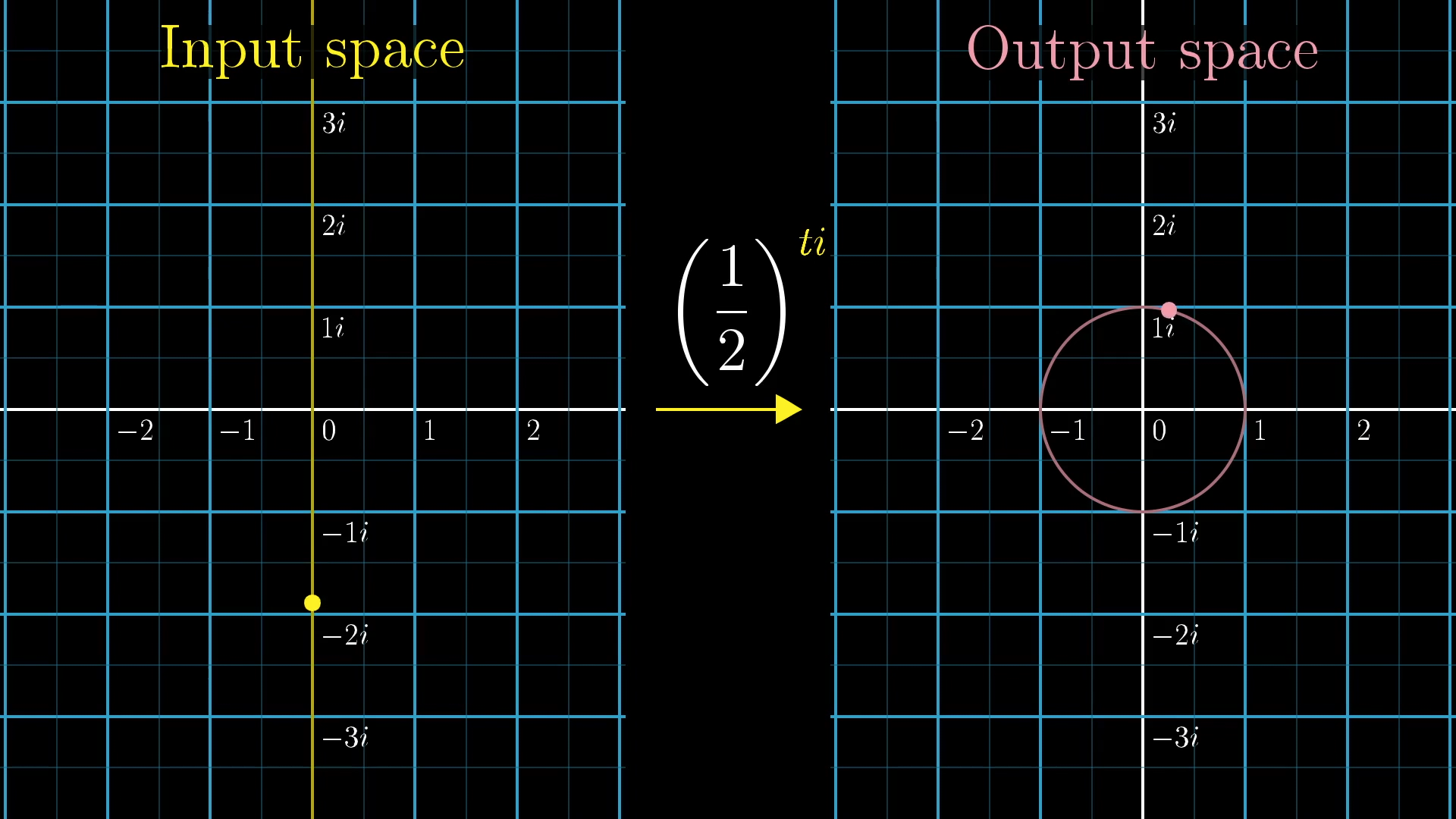

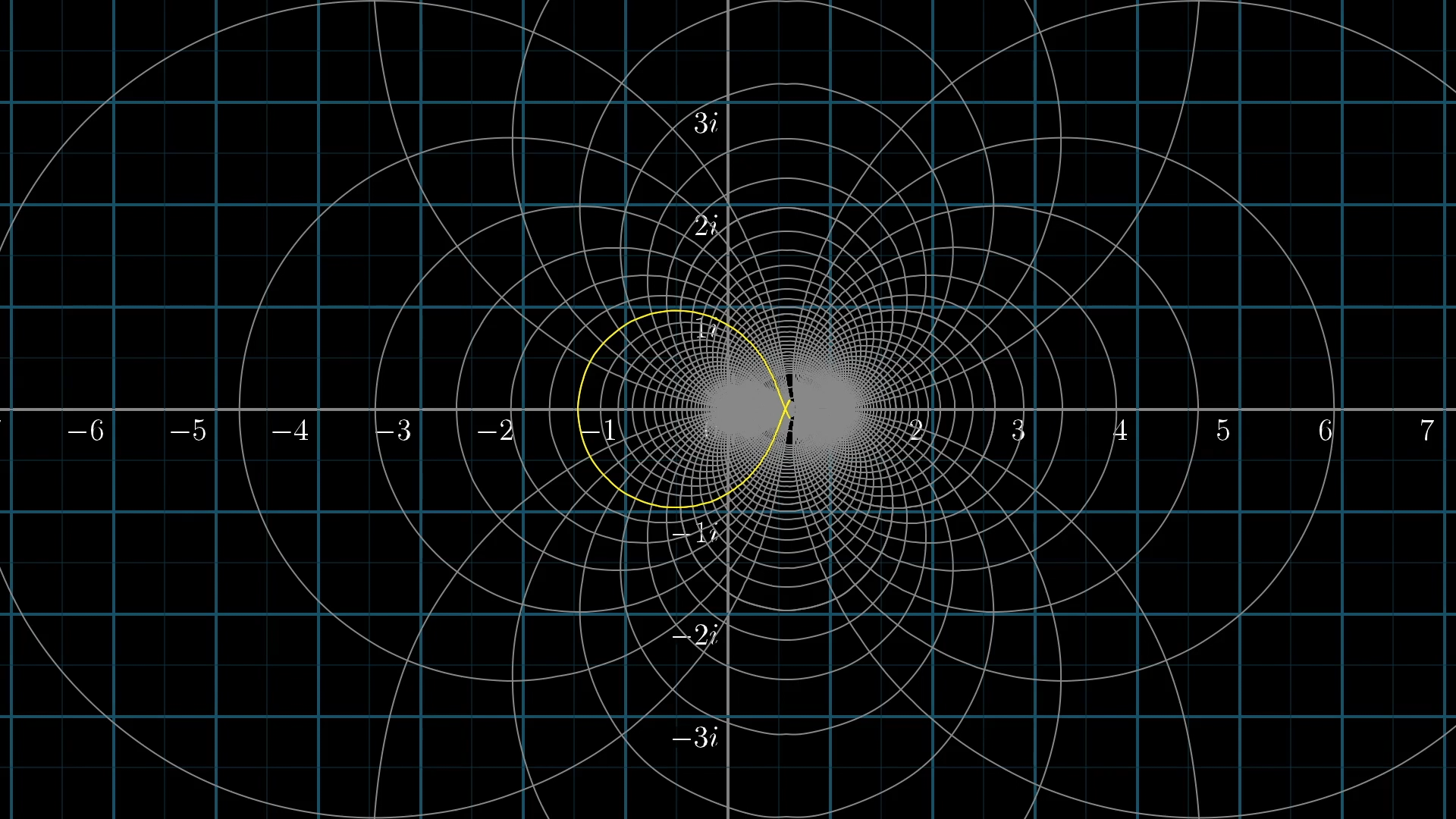

The term is familiar real number exponentiation, no issues there. But what about raising something to a pure imaginary number? If you want to really understand this, I've made several other lessons on this very question. The upshot is that when you raise to the power of a purely imaginary number, which is to say for a real value , the result sits on the unit circle in the complex plane.

As you let that pure imaginary input walk up and the imaginary line, the resulting output walks around the unit circle. For a base like , this output walks around the unit circle somewhat slowly. For a base farther away from , like , then as you let the input walk up and down the imaginary axis, the corresponding output would walk around the unit circle more quickly.

is not repeated multiplication

What does this mean for our purposes? I you take an expression like

that part has an absolute value of 1, sitting on the unit circle. Therefore multiplying by it doesn’t change the size of the number; the final result will still have a length of , it's just rotated in the complex plane.

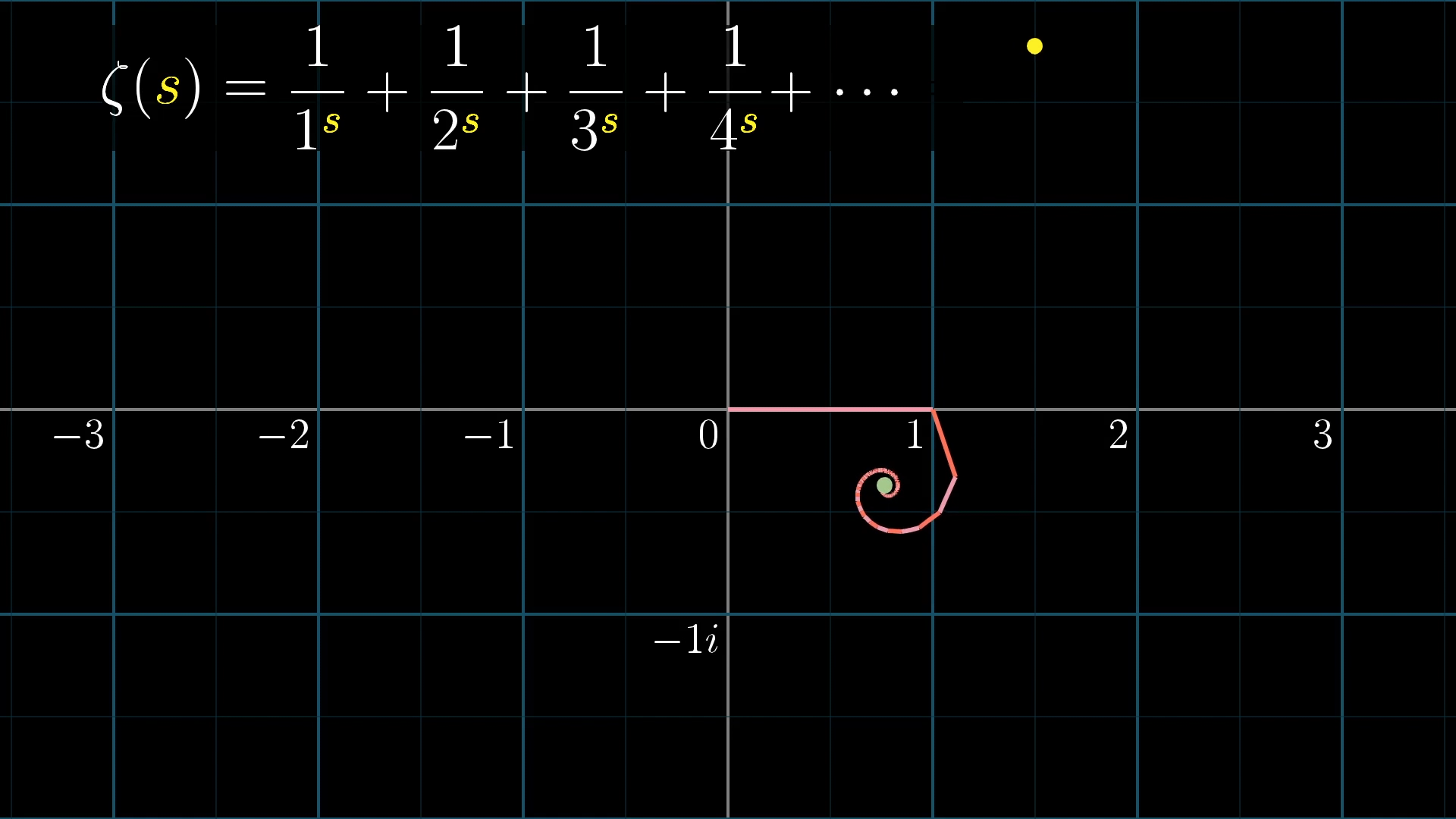

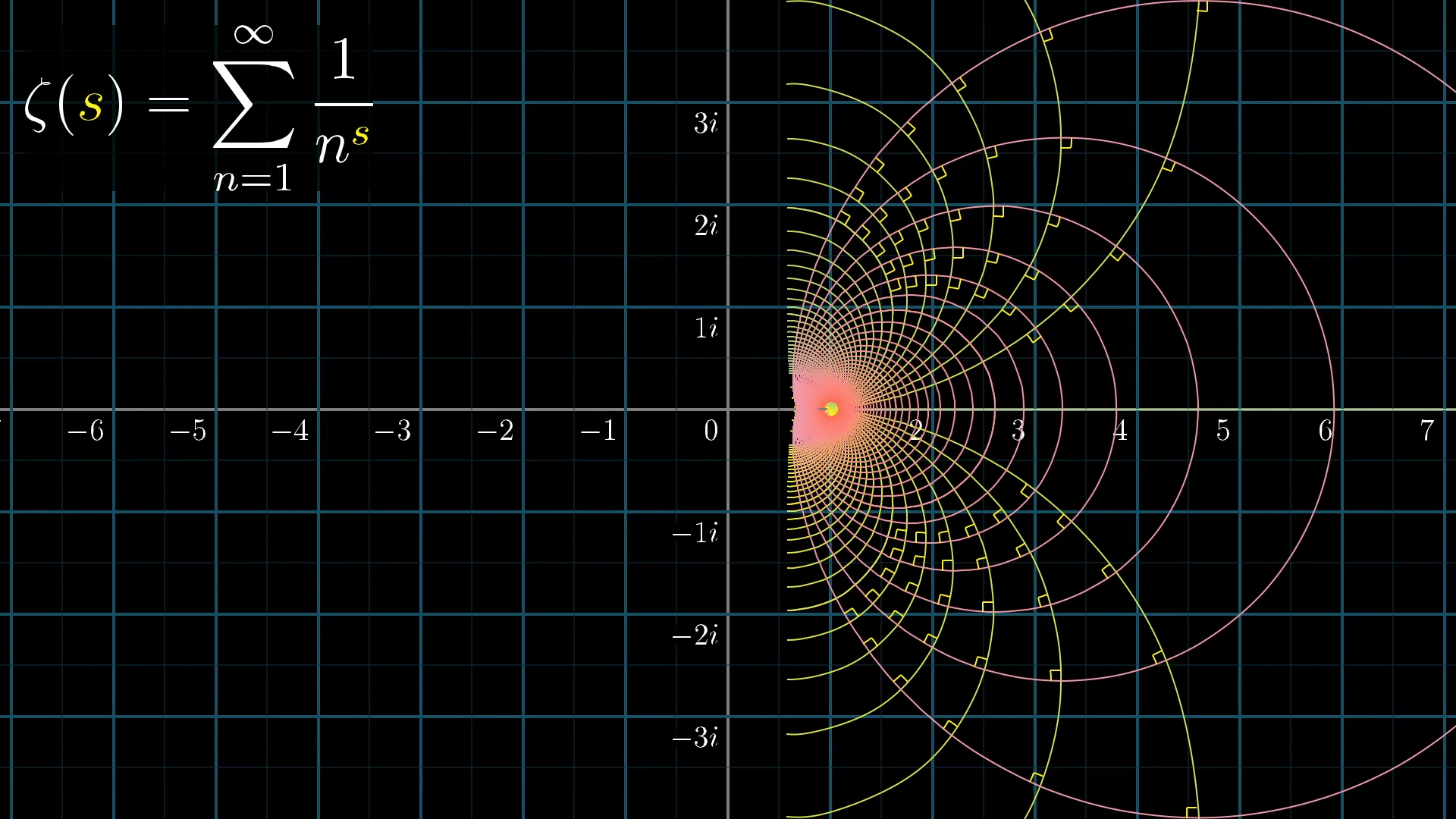

This offers a very beautiful way to think about plugging in into the zeta function. Start by thinking of each term , , , etc., perhaps visualized as little lines whose lengths are the reciprocals of square numbers.

Once you change the input from 2 to 2+i, each of these lines will get rotated by some amount. The amount that each term is rotated depends on , and the larger the value of , the more the rotation, which results in a kind of spiral for our new sum.

Importantly, the lengths of those lines won’t change, so this sum still converges, it just does so in a spiral to some specific point on the complex plane which is no longer a real number.

Given that , what does equal to?

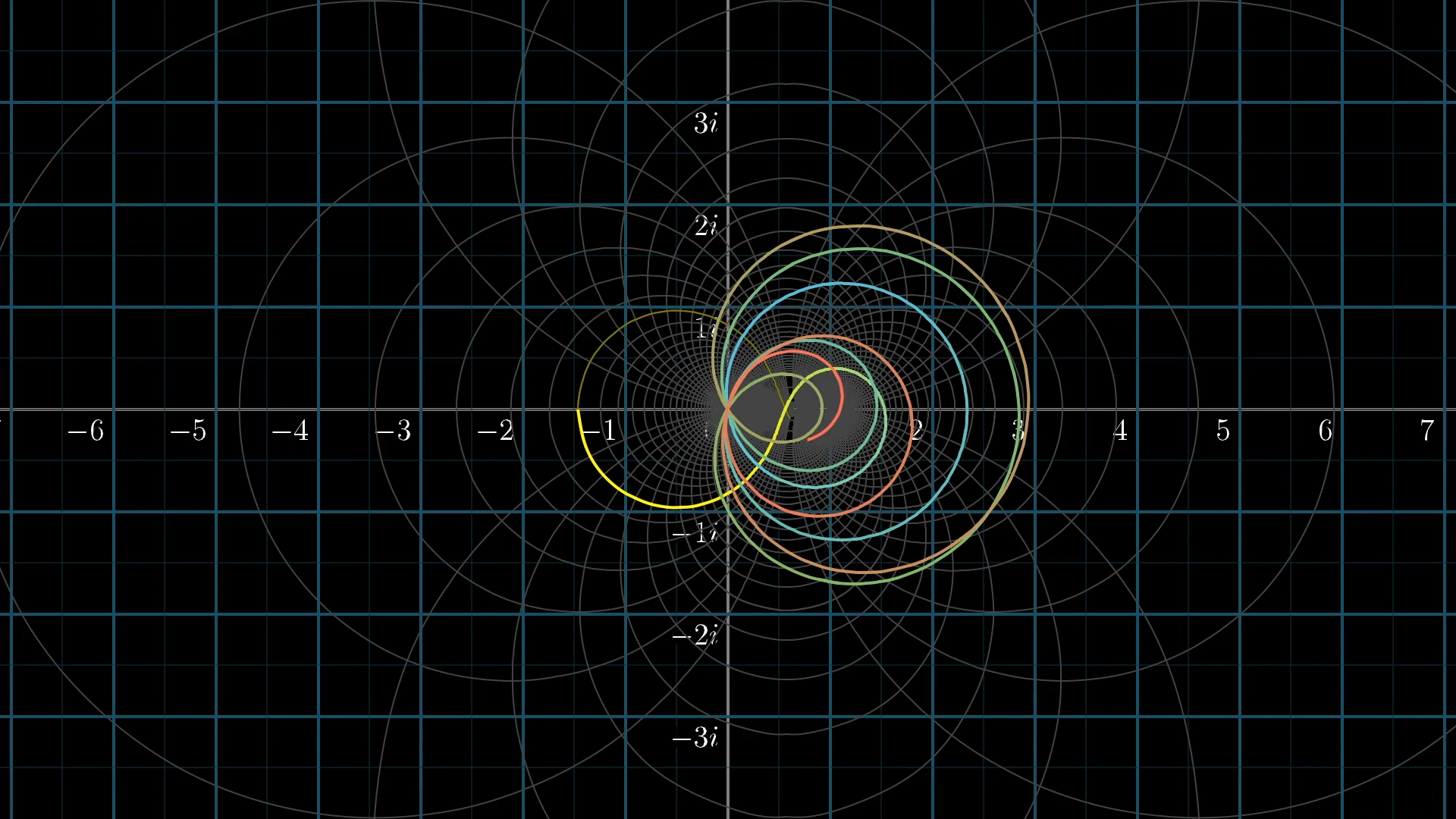

Let's see what it looks like if we vary the input s, represented with a yellow dot, and follow the effect on the spiral sum converging to some output .

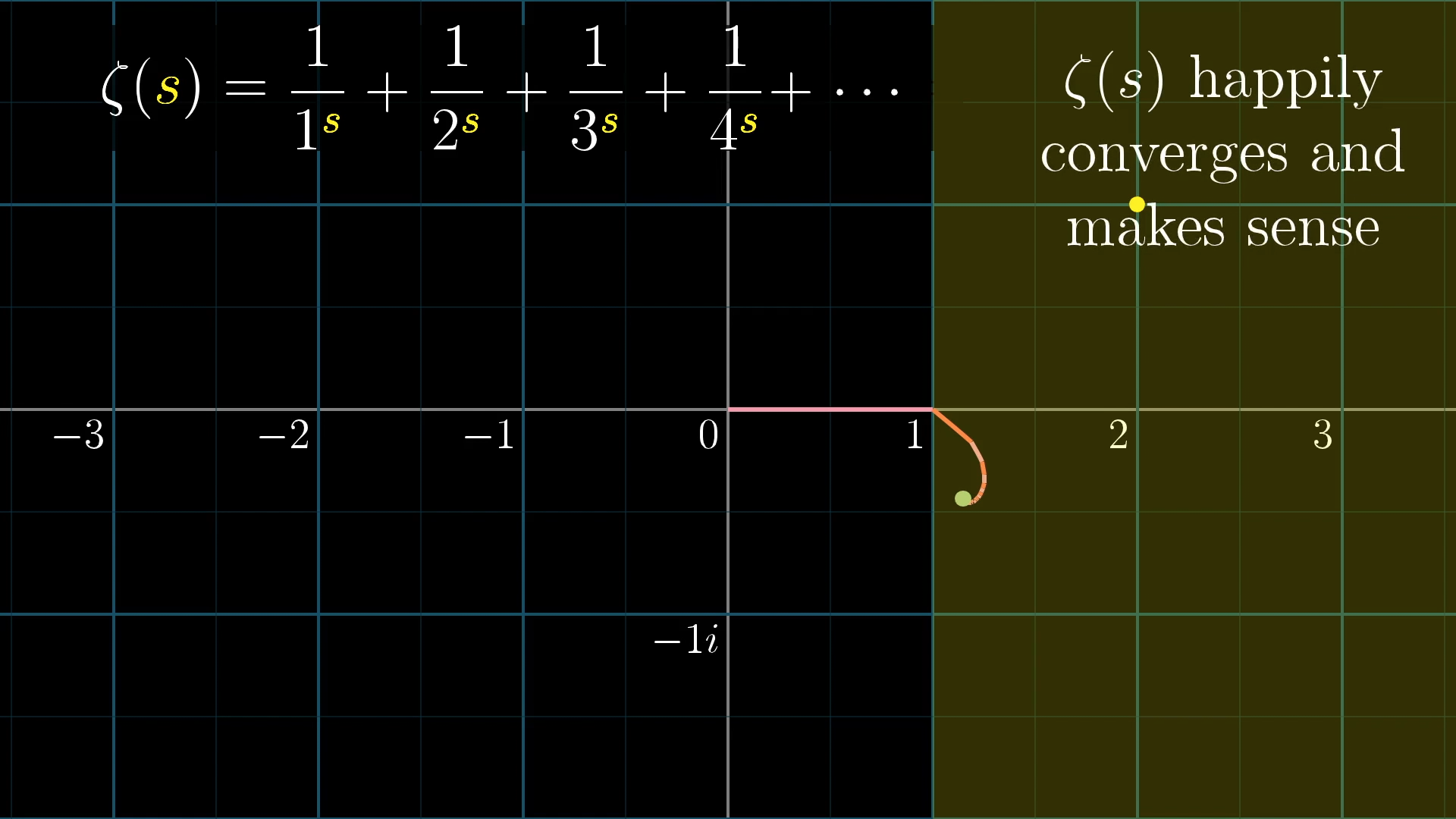

What this means is that , defined as the infinite sum , is a perfectly reasonable complex function as long as the real part of the input is greater than 1, meaning the input sits somewhere on this right half of the complex plane.

Again, this is because it’s the real part of that determines the size of each term in this sum, and those sizes determine whether the sum converges. Well, that's not exactly true, in principle once rotation enters the game you could get some cancelation. For example the sum

diverges, but if we rotate every other term , getting the alternating series

it then converges. However, in the case of the zeta function the rotation applied to terms where the real part of is less than is not enough to make it converge. In the jargon, we'd say this sum converges if and only if it's absolutely convergent.

Visualizing Complex Functions

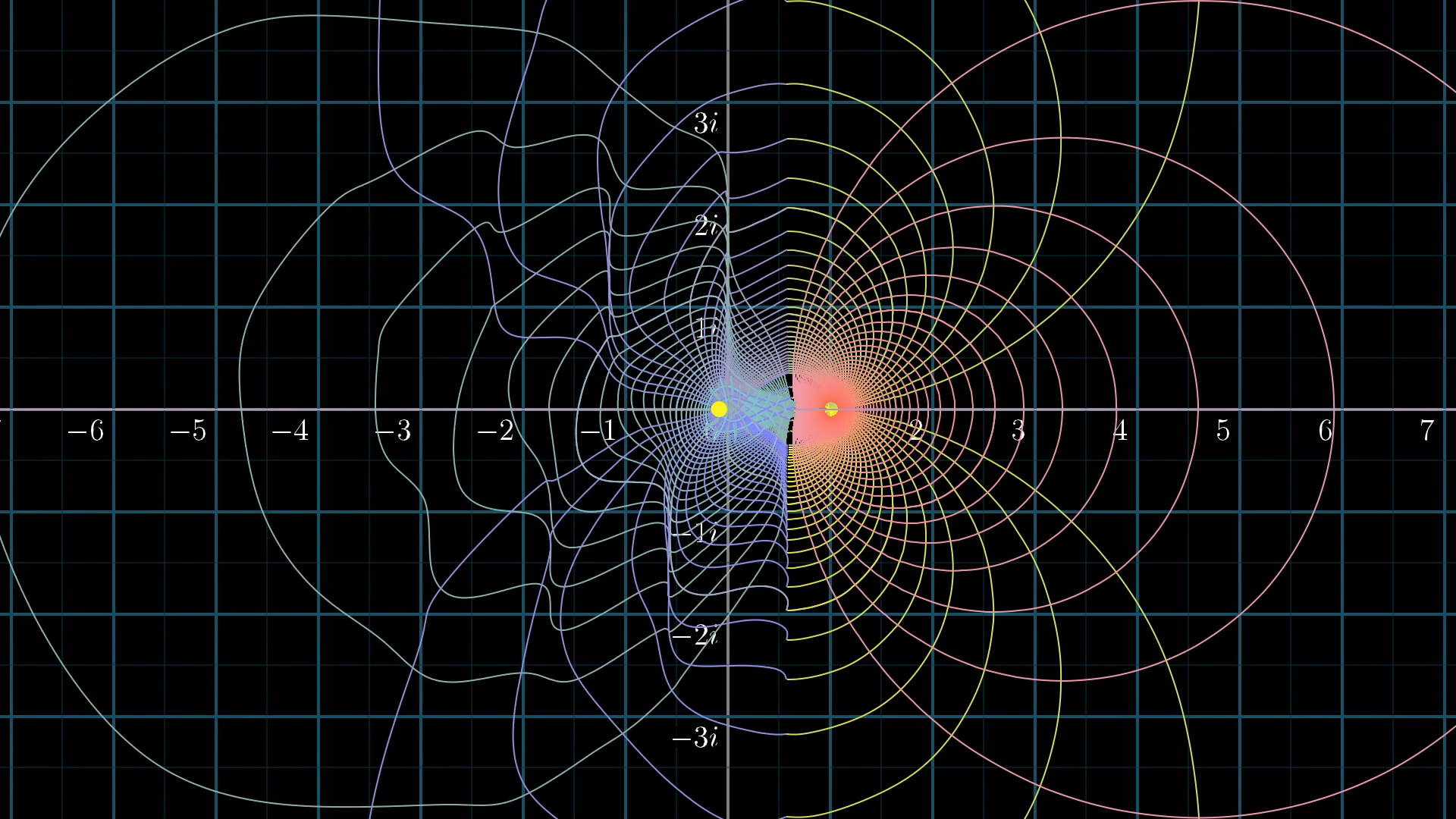

Let's try visualizing this function. It takes in inputs on this right half of the complex plane, and spits out outputs somewhere else on the complex plane. A nice way to understand complex functions is to picture them as transformations, meaning you look at each input to the function, and let it move over to its corresponding output.

How can we visualize this for all complex inputs?

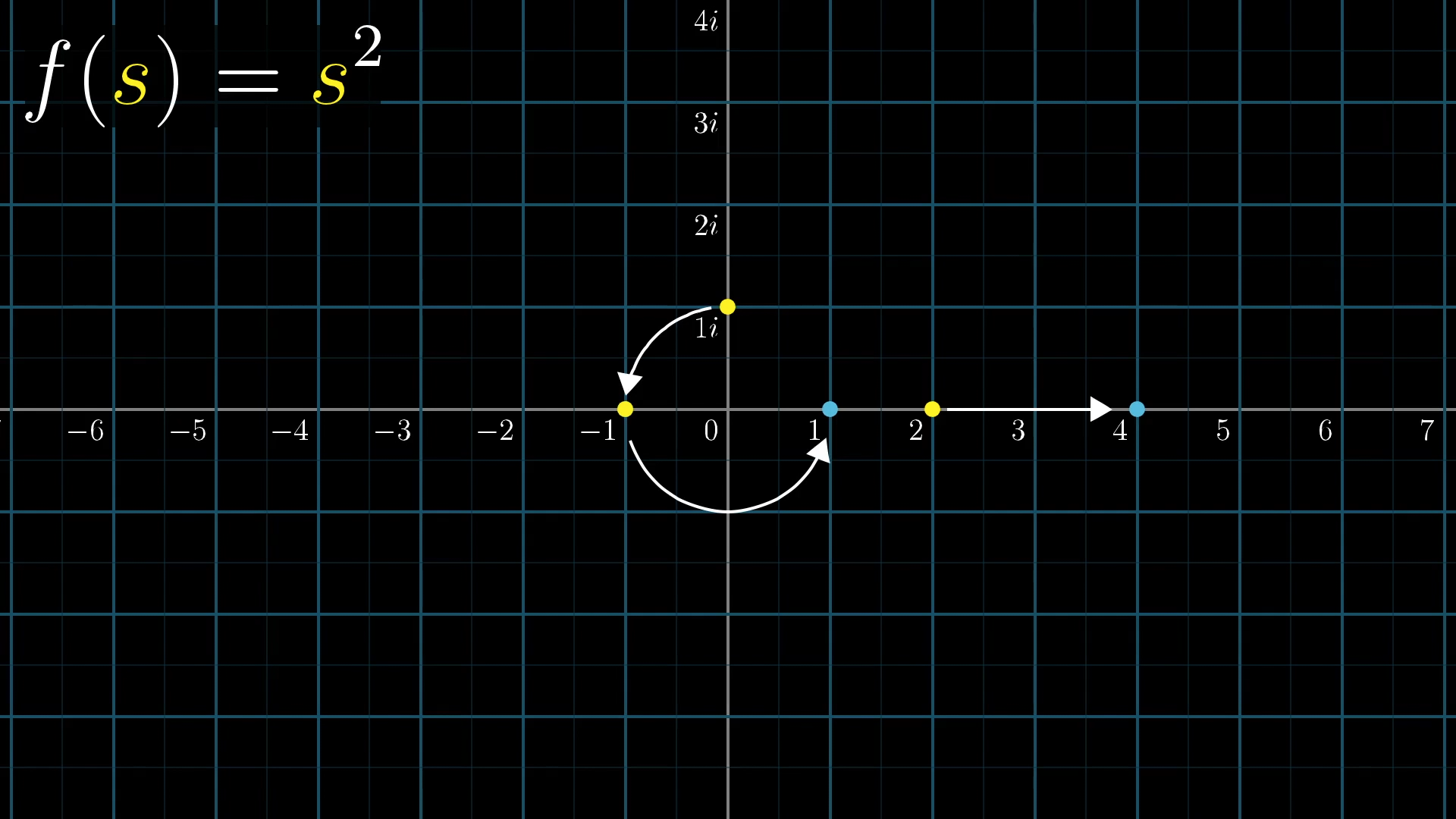

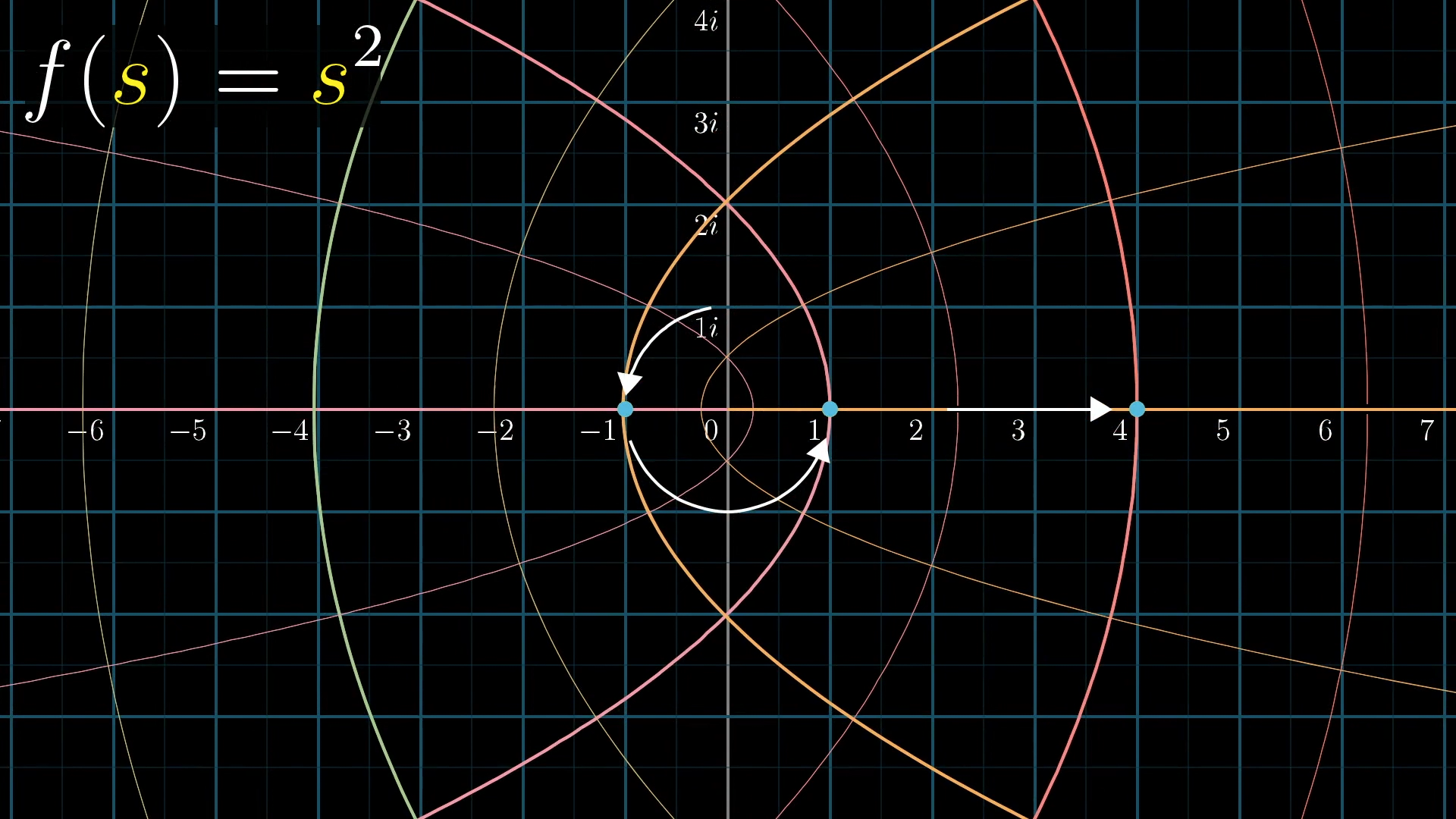

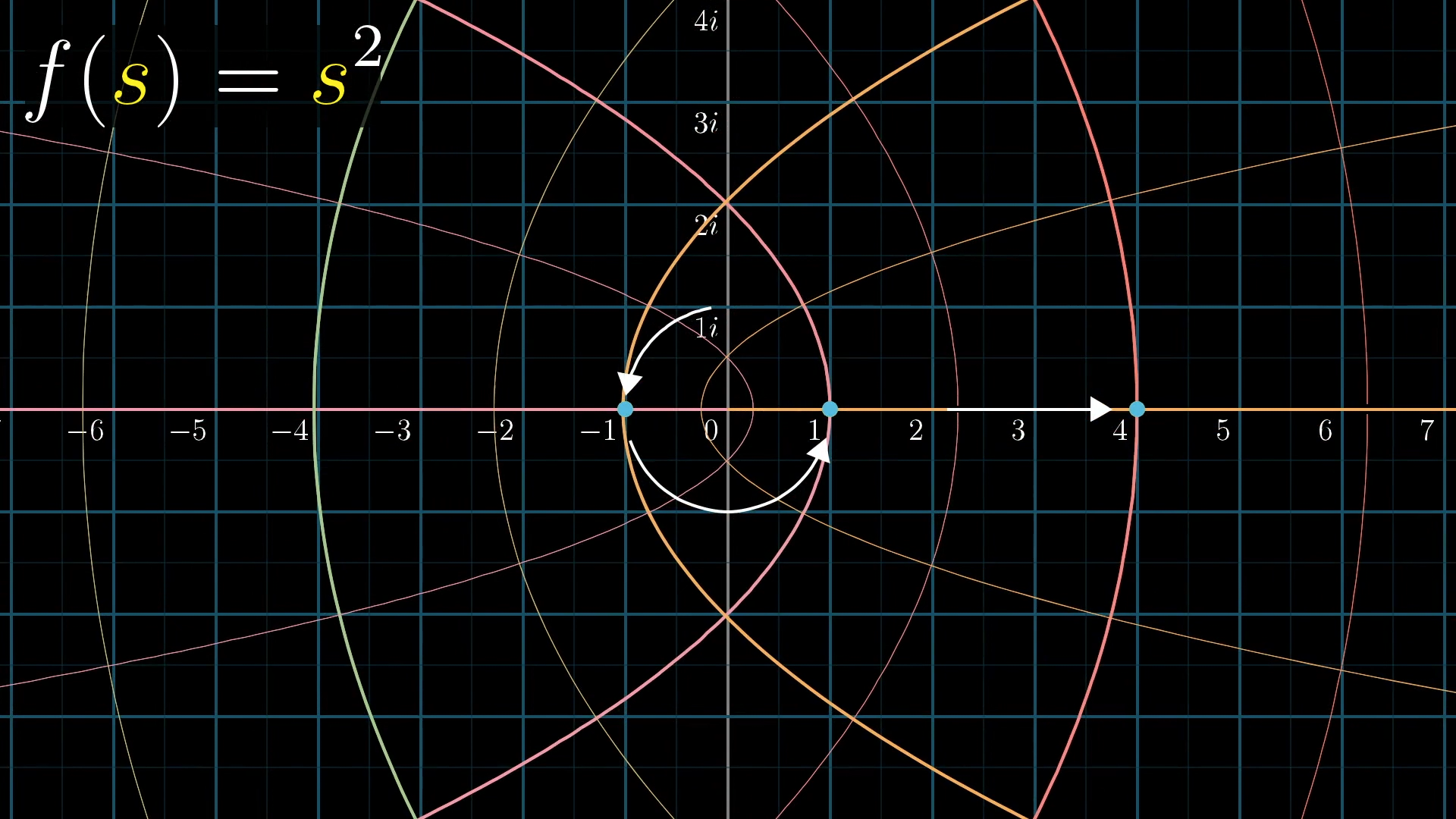

For example, let’s take a moment to try visualizing something a little easier than the zeta function. Say . When you plug in , you get , so we’ll end up moving the point at over to . When you plug in , you get , so the point at will end up moving over to 1. When you plug in , by definition its square is , so it’s going to move to .

If , what is?

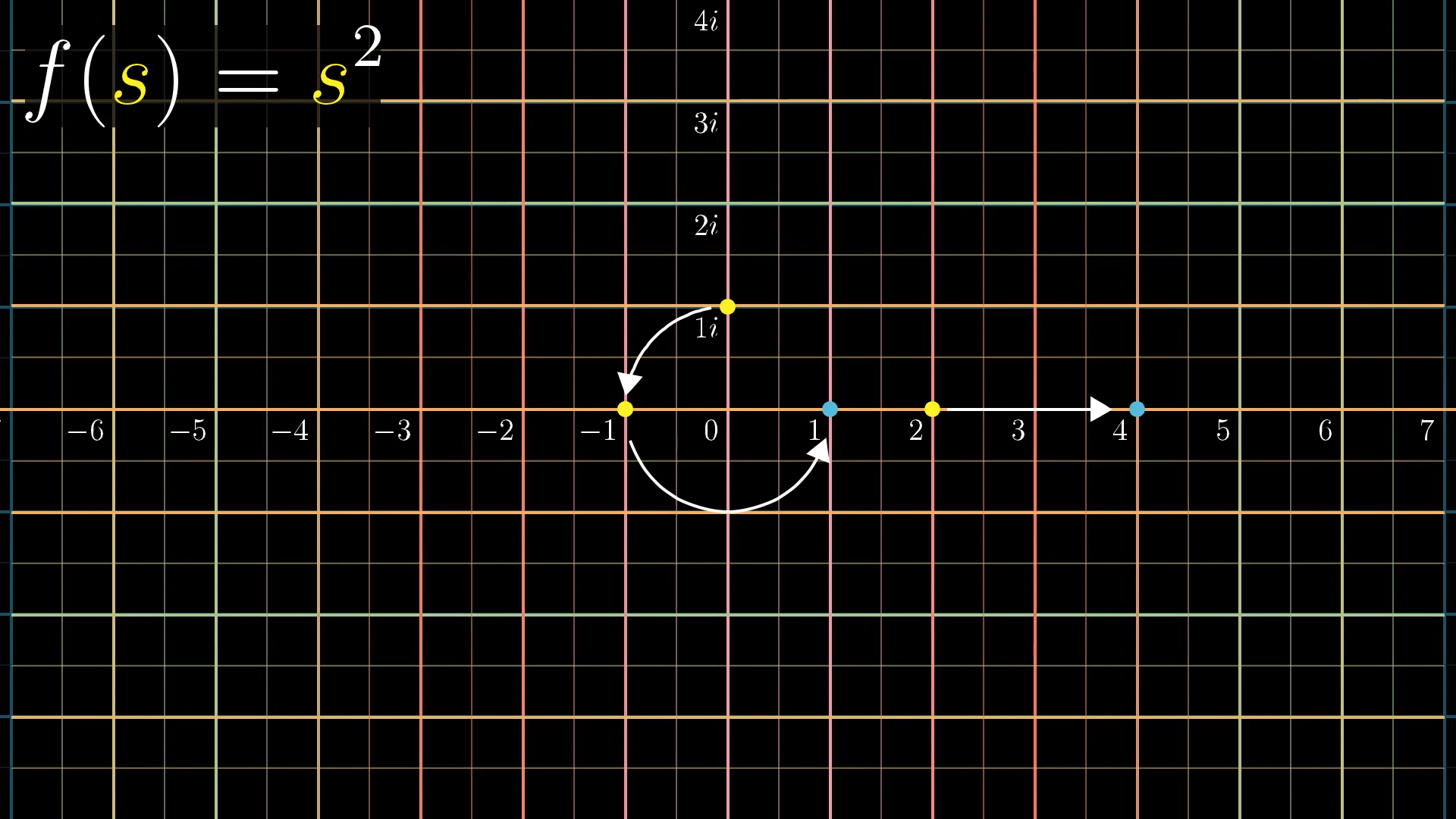

Let's add a more colorful grid, since things are about to start moving and it’s nice to have something to distinguish grid lines during this movement.

I’ll tell the computer to move every point on this grid over to its corresponding output under the function . Here’s what it looks like.

Focus on one of the yellow points, and notice how it moves to the blue point corresponding to its square.

It’s a bit complicated to see all points moving all at once, but the reward is that it gives a very rich picture for what a complex function is doing, and it all happens in two-dimensions.

Analytic Continuation

Back to the zeta function. We have this infinite sum, which is a function of a complex number , and we feel good and happy about plugging in values of whose real part is greater than 1, and getting some meaningful output via some converging spiral sum.

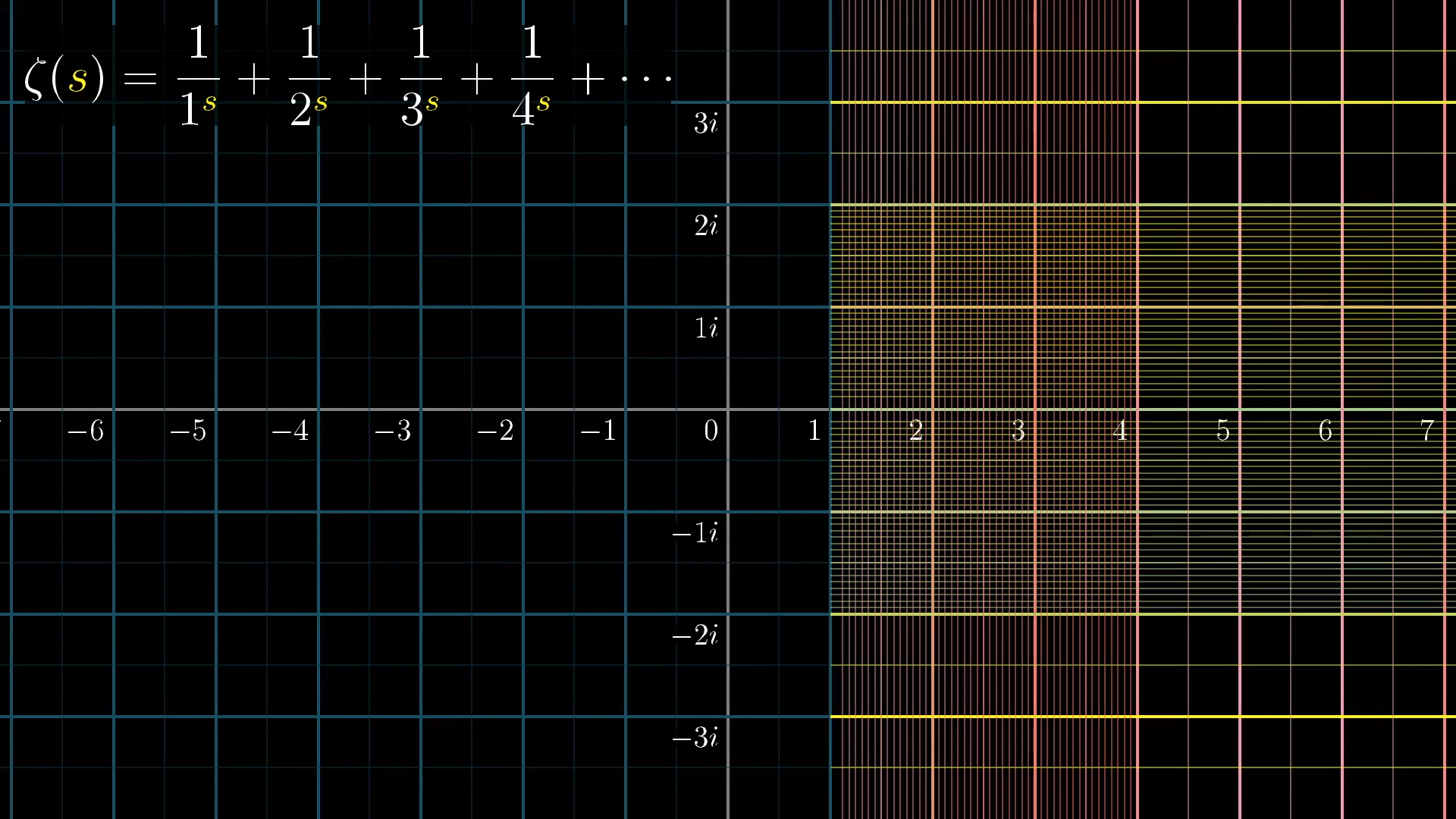

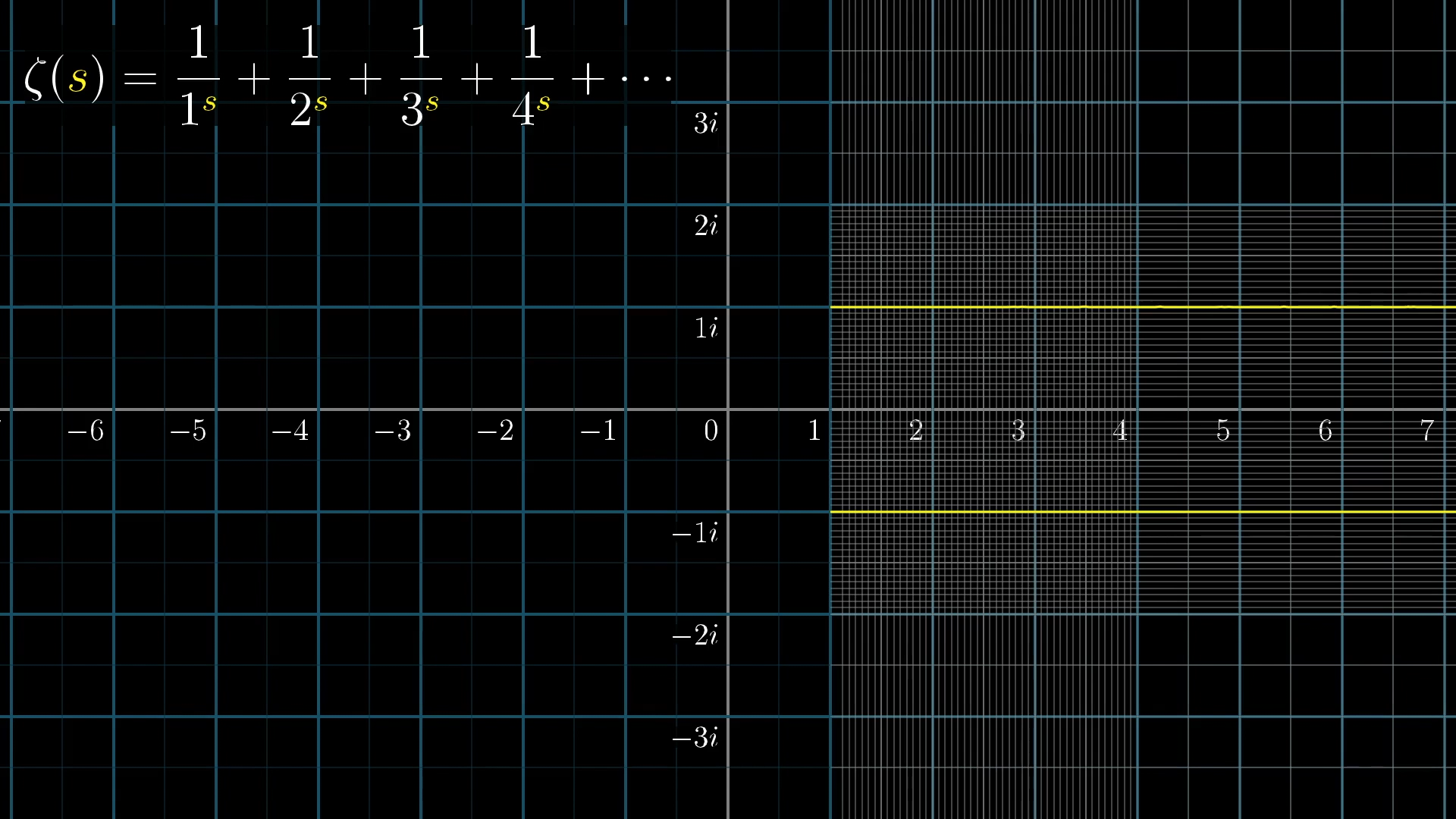

To visualize this, let's begin with a portion of the grid sitting on the right side of the complex plane here, with real part greater than 1, like this:

We've added more lines near 1, since it gets stretched out

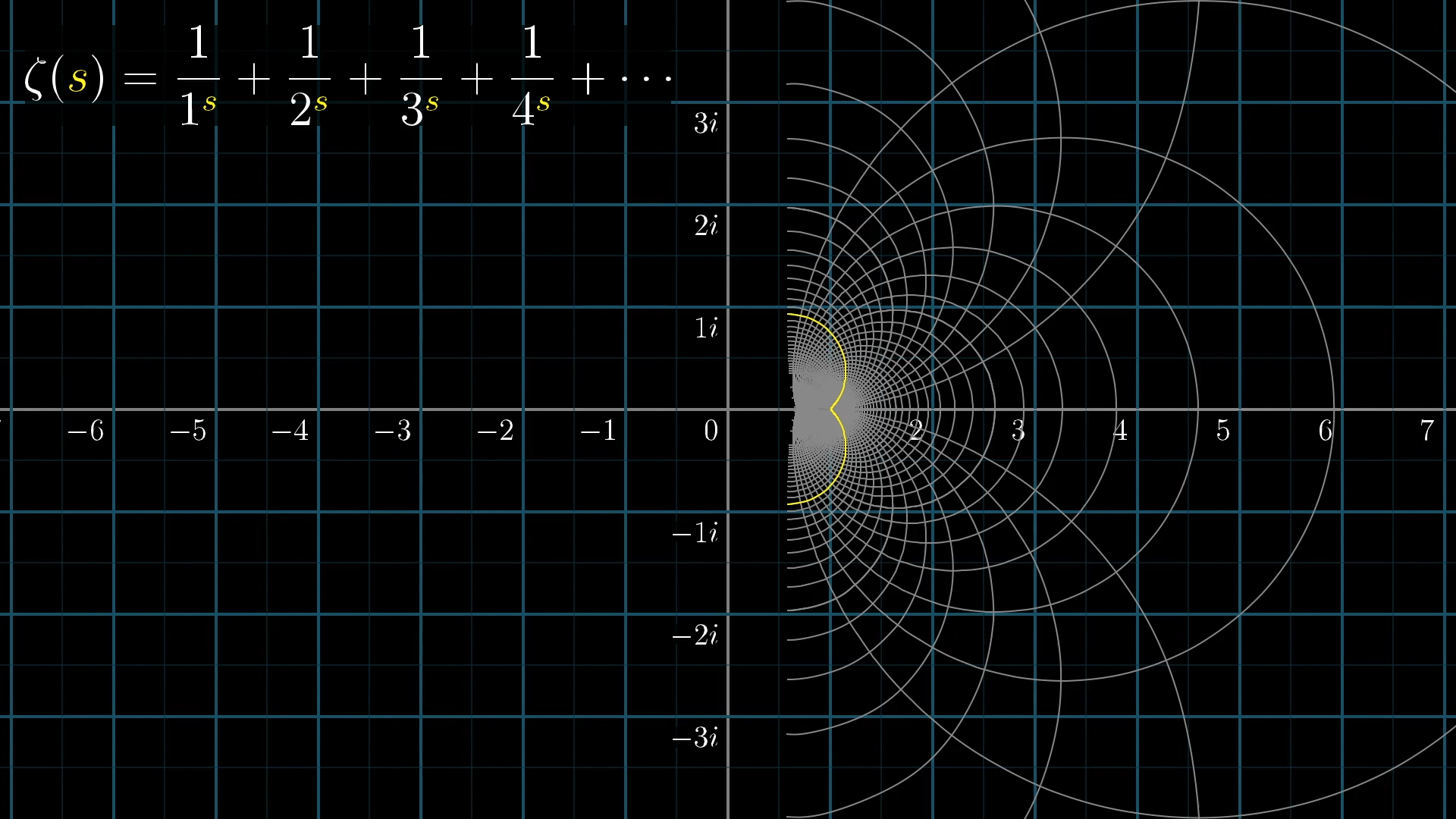

Again, I'll tell the computer to move each point of this grid to the appropriate output; the place where this sum converges when you set s equal to the complex number at that point.

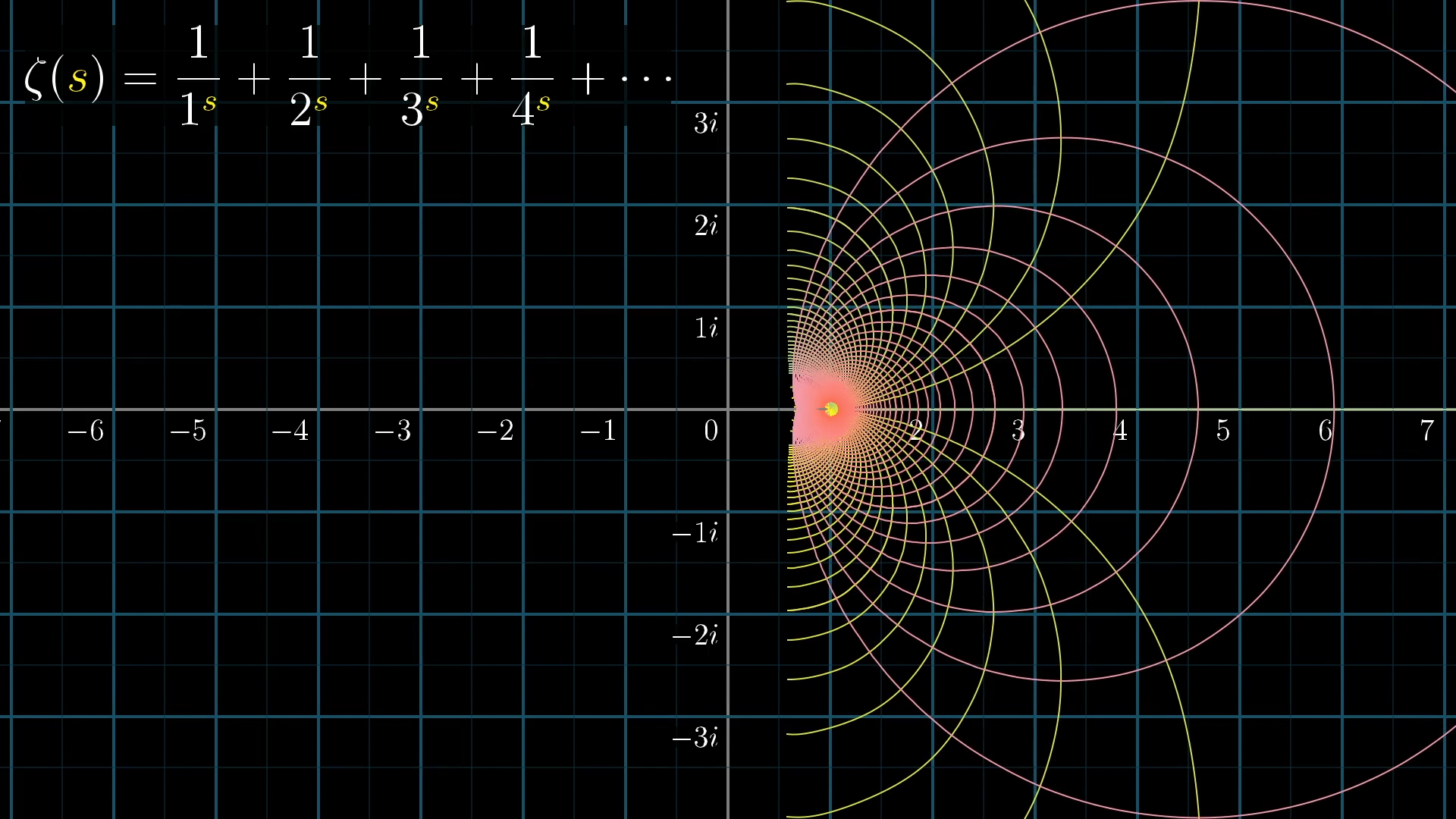

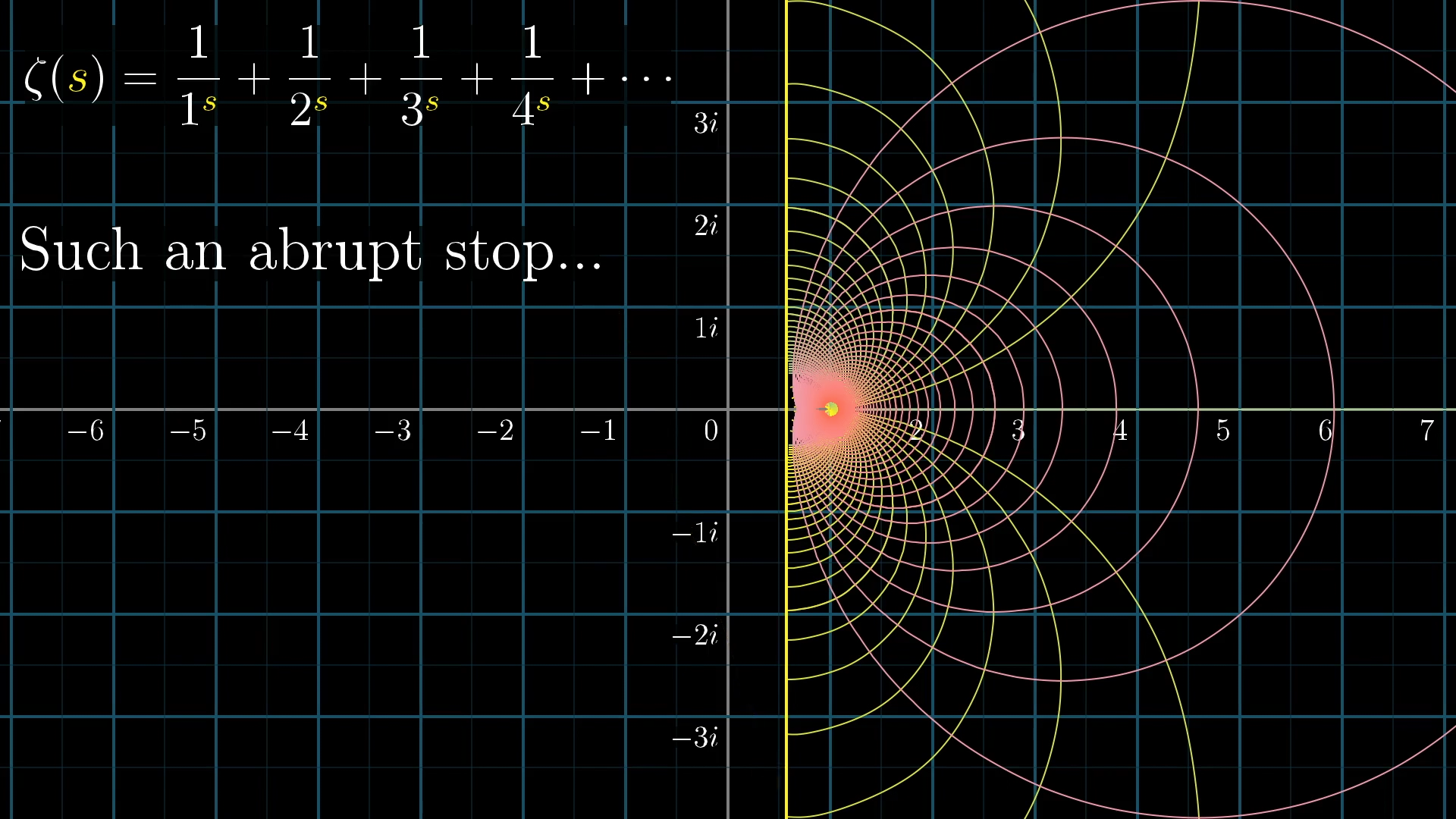

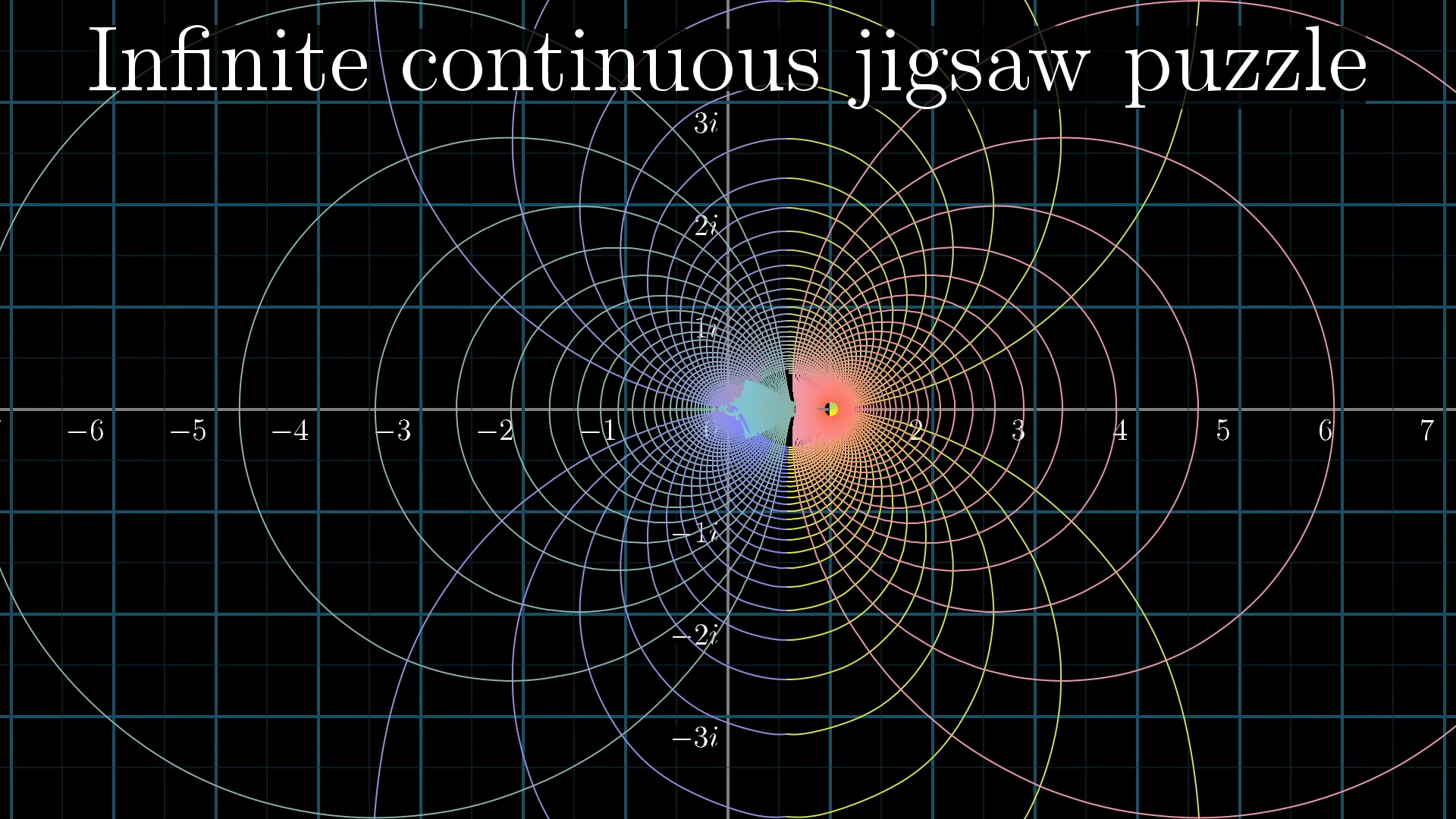

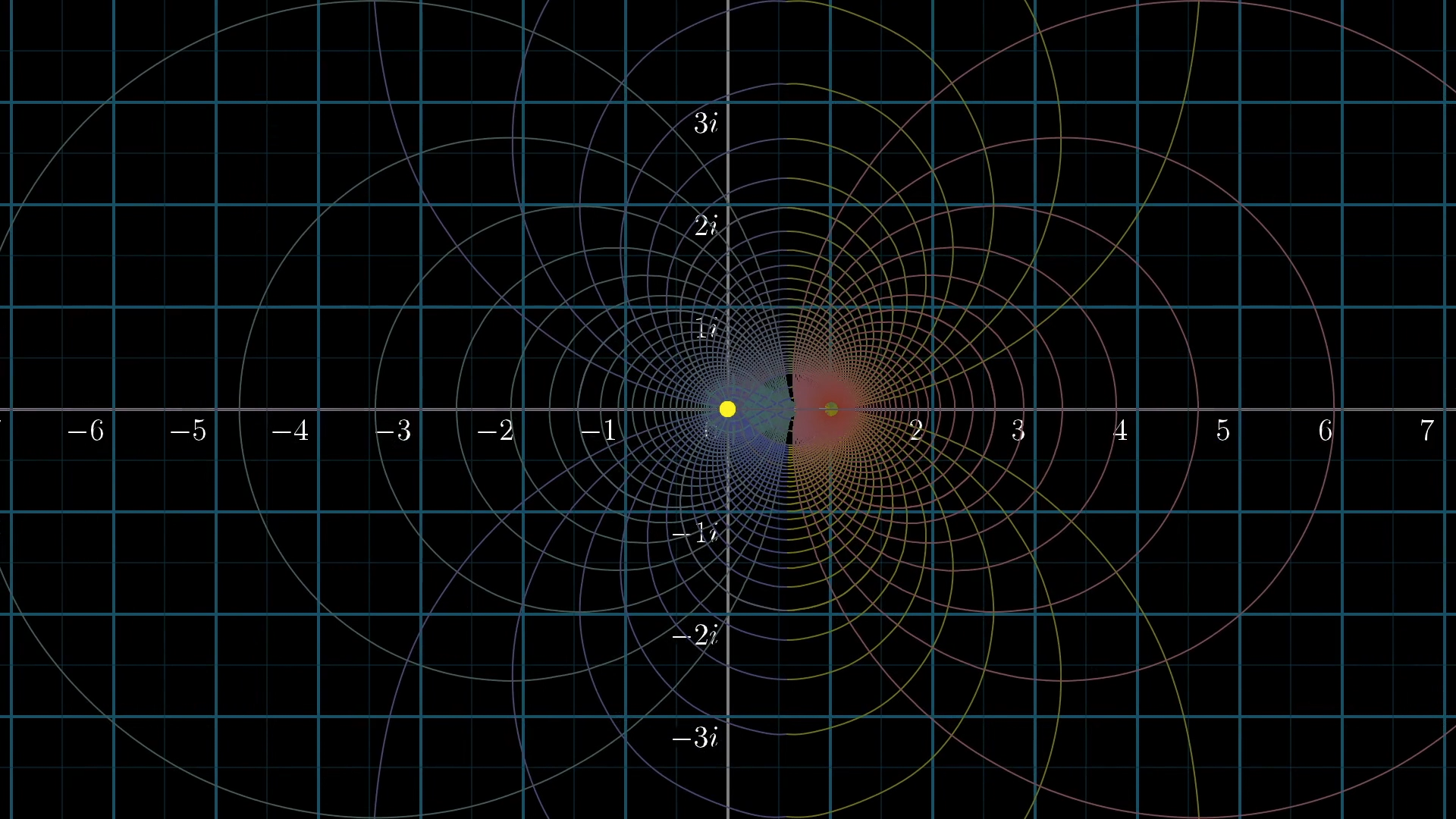

First of all, can we all take a moment to appreciate how beautiful this is? If this doesn’t make you want to learn more about complex functions, you have no heart! But more pertinently for our final aim today, this transformed grid is just begging to be extended a little bit .

Damn!

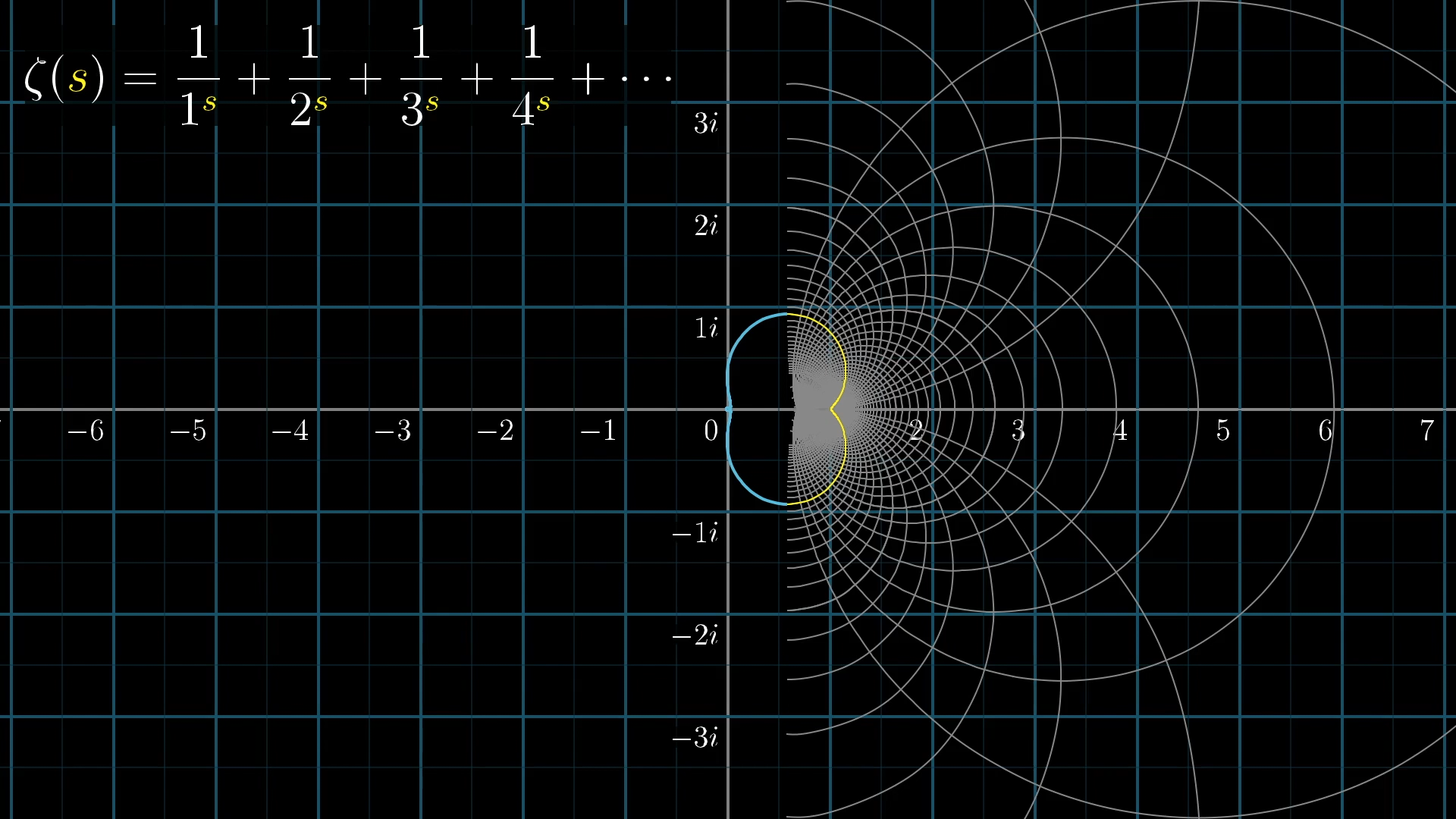

For example, let’s highlight two lines representing all complex numbers with imaginary part or .

After the transformation, these lines make such lovely arcs before they abruptly stop.

Don’t you just want to, you know, continue those arcs.

In fact, you can imagine how some altered version of the function, with a definition extended into the left half of the plane, might be able to complete this picture, which otherwise seems so arbitrarily cut off.

Well, this is exactly what mathematicians working with complex functions do; they continue the function beyond the original domain where it was defined.

As soon as we start talking about inputs where the real part is less than 1, the infinite sum we saw before doesn’t make sense anymore. You’ll get nonsense like adding But just looking at this transformed version of the right half of the plane, where the sum does make sense, it’s begging us to extend the set of points we’re considering as inputs, even if it means defining the extended function in some way which doesn’t necessarily use that sum.

How to extend?

Of course, the question is then how to define the function on the rest of the plane. You might think you could extend this function in any number of ways. Maybe you define an extension that makes it so that the input point at, say, land on , but maybe you squiggle some extension that makes it land on any other value.

As soon as you open yourself up to the idea of defining the function differently for values outside that domain of convergence, the world is your oyster and you can have any number of extensions...right?

Well...not exactly. I mean yes, you can give any child a marker and have them extend these lines any which way, but if you add the restriction that the new extended function has a derivative everywhere, it (rather surprisingly!) locks us into one and only one possible extension.

What's the derivative of a complex function?

"Derivatives," I hear you ask, "for a complex function?" Luckily, there's a very approachable geometric intuition you can keep in mind for when I say a phrase like “has a derivative everywhere”.

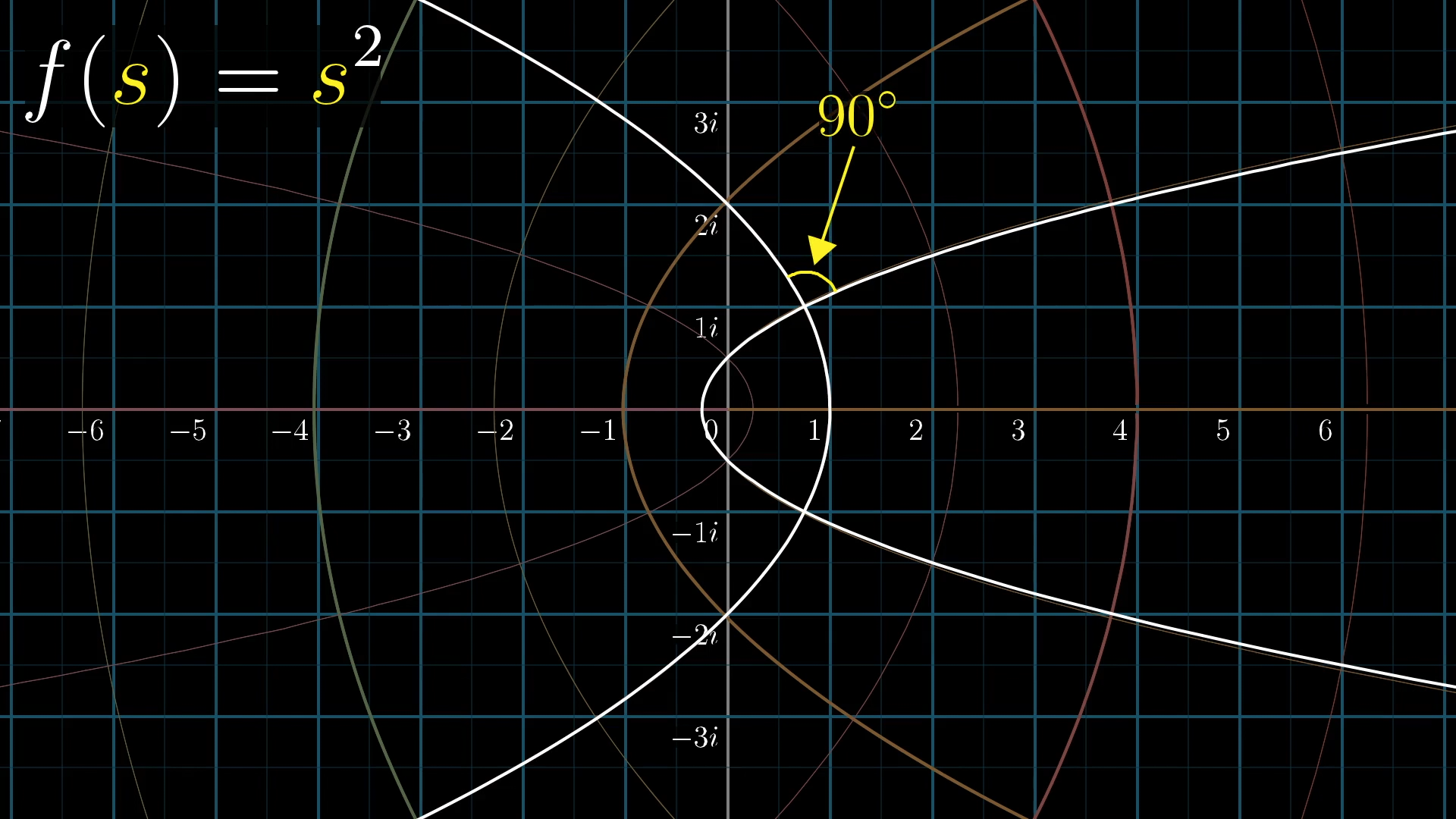

Let’s go back to that example. Again, we’ll think of this function as a transformation, moving every point s of the complex plane to the point .

For those of you who know calculus, you know you can take the derivative of at any input.

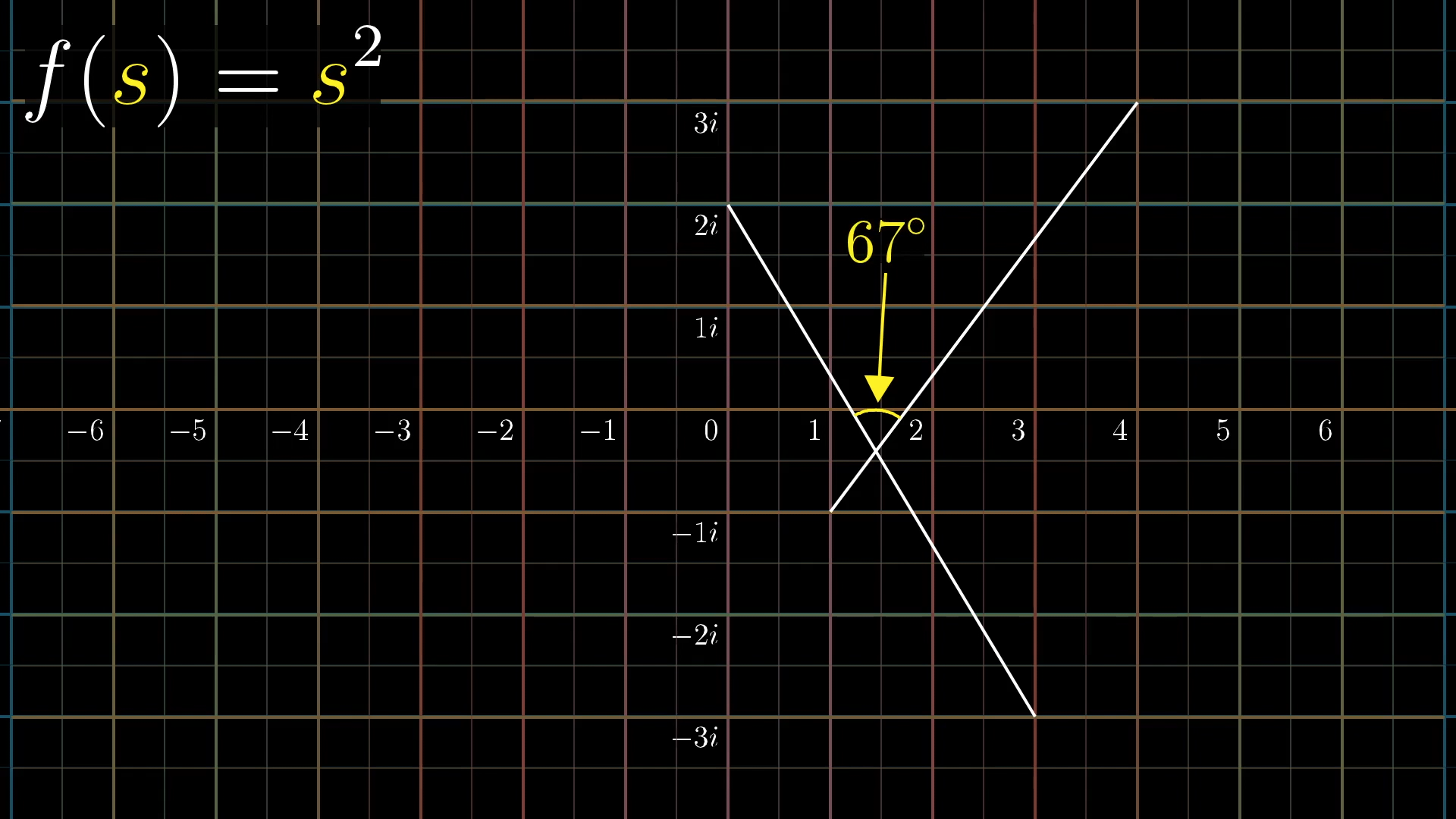

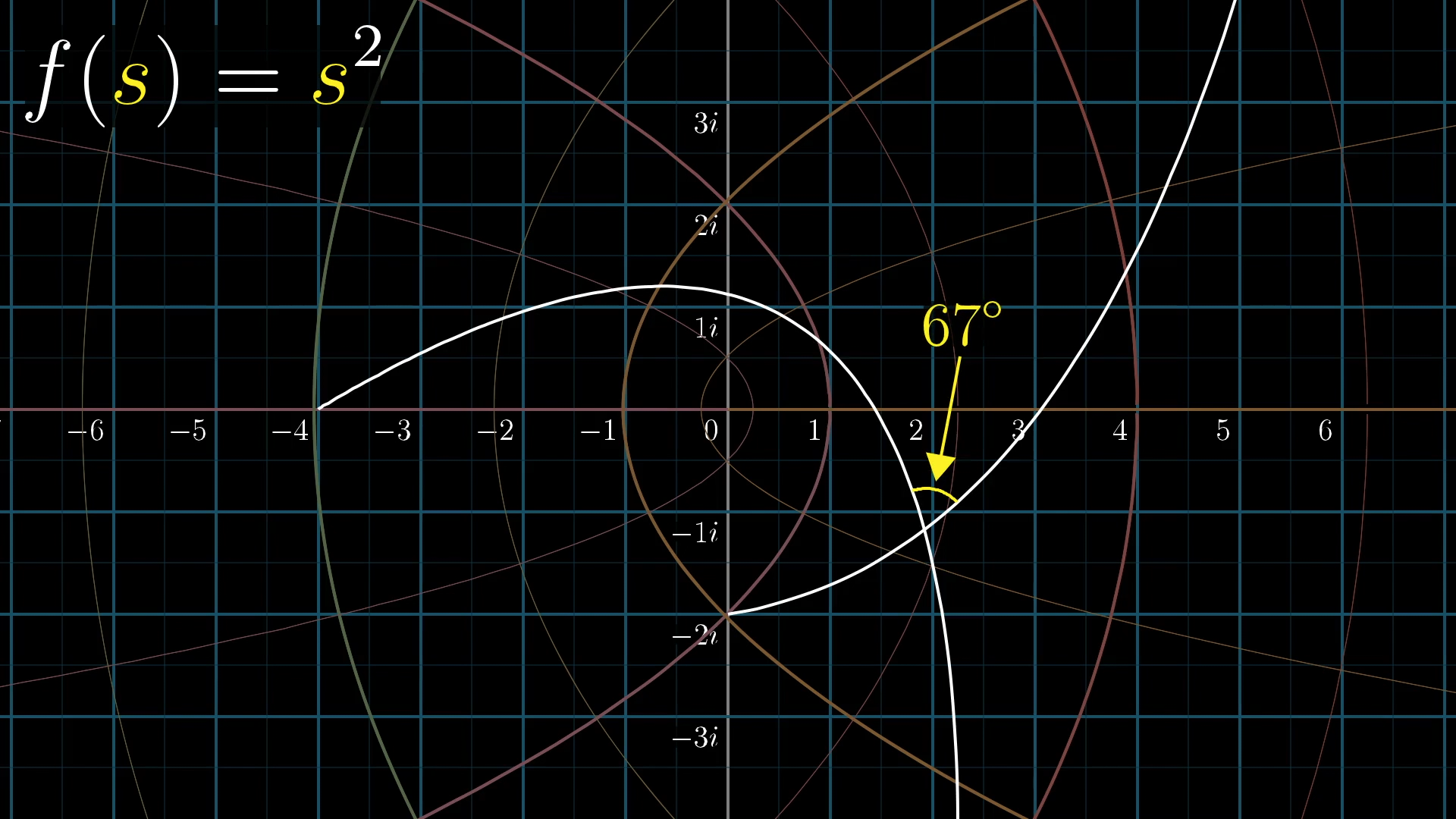

But here’s an interesting property of the transformation that turns out to be more or less equivalent to that fact. If you look at any two lines in the input space that intersect at a certain angle, and consider what they turn into after the transformation, they will still intersect each other at that same angle.

For instance, consider this pair of lines before transformation. They make an angle of .

Now, take a look at the same lines and the angle they make after applying the transformation .

The lines might get curved, but the important part is that the angle at which they intersect remains unchanged. And this is true for any pair of lines you choose! When I say a function “has a derivative everywhere”, I want you to think about this angle-preserving property: Anytime two lines intersect, the angle between them remains unchanged after the transformation. If you're curious about the lingo, we call functions with this property "conformal mappings".

At a glance, this is easiest to appreciate by noticing how all curves that the grid lines turn into still intersect each other at right angles.

Functions that have a derivative everywhere are called analytic, so you can think of this word “analytic” as meaning “angle-preserving”.

Admittedly, I’m lying to you a little here, but only a little. A slight caveat, for those of you here who want the full details, is that at inputs where the derivative of a function is 0, instead of angles being preserved, they get multiplied by some integer. Those points are by far the minority, and for almost all inputs to an analytic function, angles are preserved. So if when I say “analytic”, you think “angle-preserving”, but you have this small caveat lurking in the back of your mind, that’s a fine intuition to have.

Preserving angles like this is incredibly restrictive you think about it. The angle between any pair of intersecting lines has to remain unchanged. And yet, many of the functions you might think to write down, polynomials, , , etc., are analytic. The field of complex analysis, which Riemann helped to establish in its modern form, is almost entirely about leveraging the highly restrictive properties of analytic functions to understand results and patterns in other fields of math and science.

Does the function , thought of as mapping of complex numbers, preserve angles?

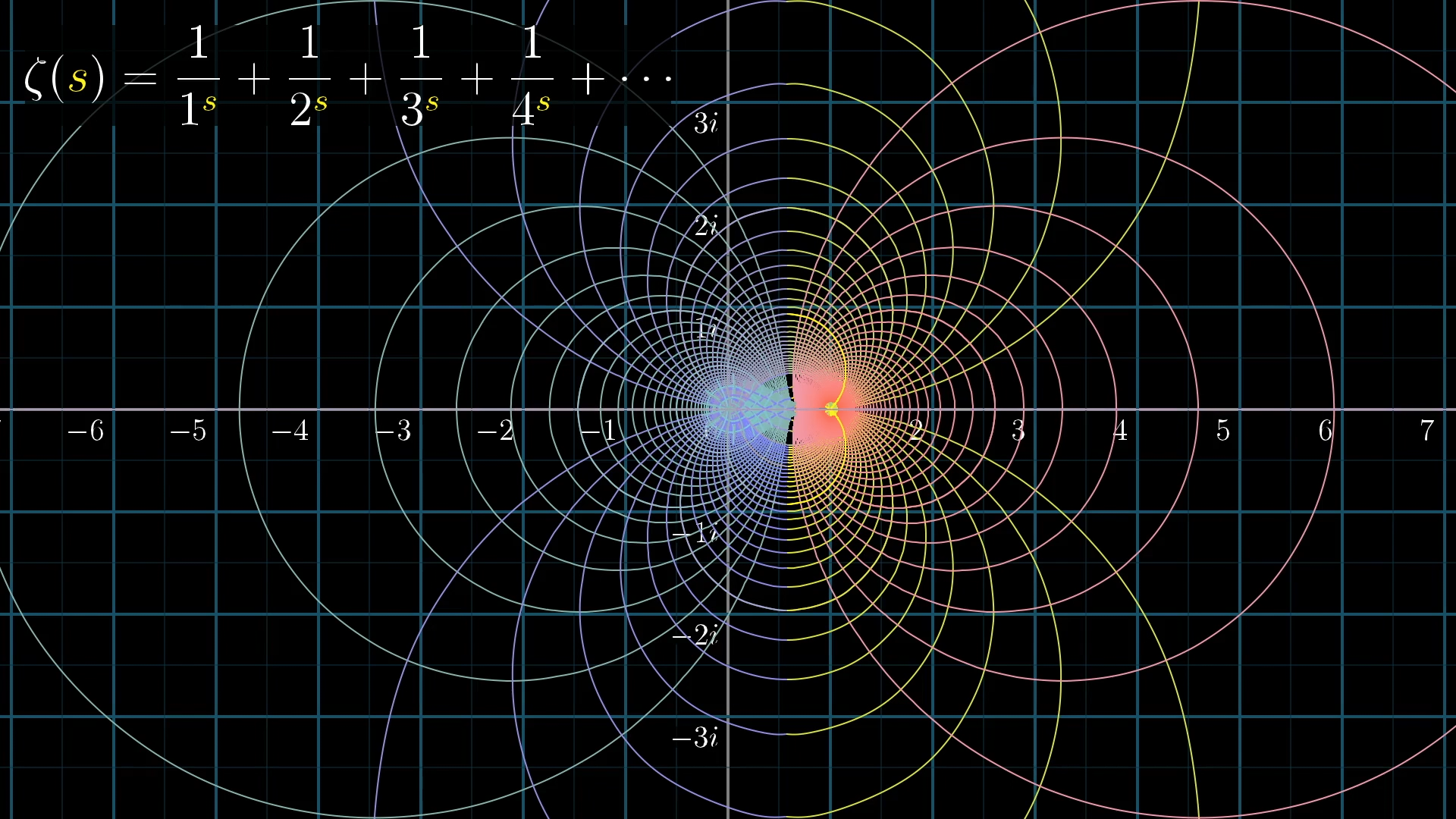

The zeta function, defined by this infinite sum on the right-half of the plane, is an analytic function. Notice how all these curves that the grid lines turned into still intersect at right angles.

The surprising fact about complex functions is that if you want to extend an analytic function beyond the domain where it was originally defined, for example extending the zeta function into the left half of the plane, then requiring that the new extended function still be analytic (that it still preserves angles everywhere) forces you into only one possible extension, if one exists at all.

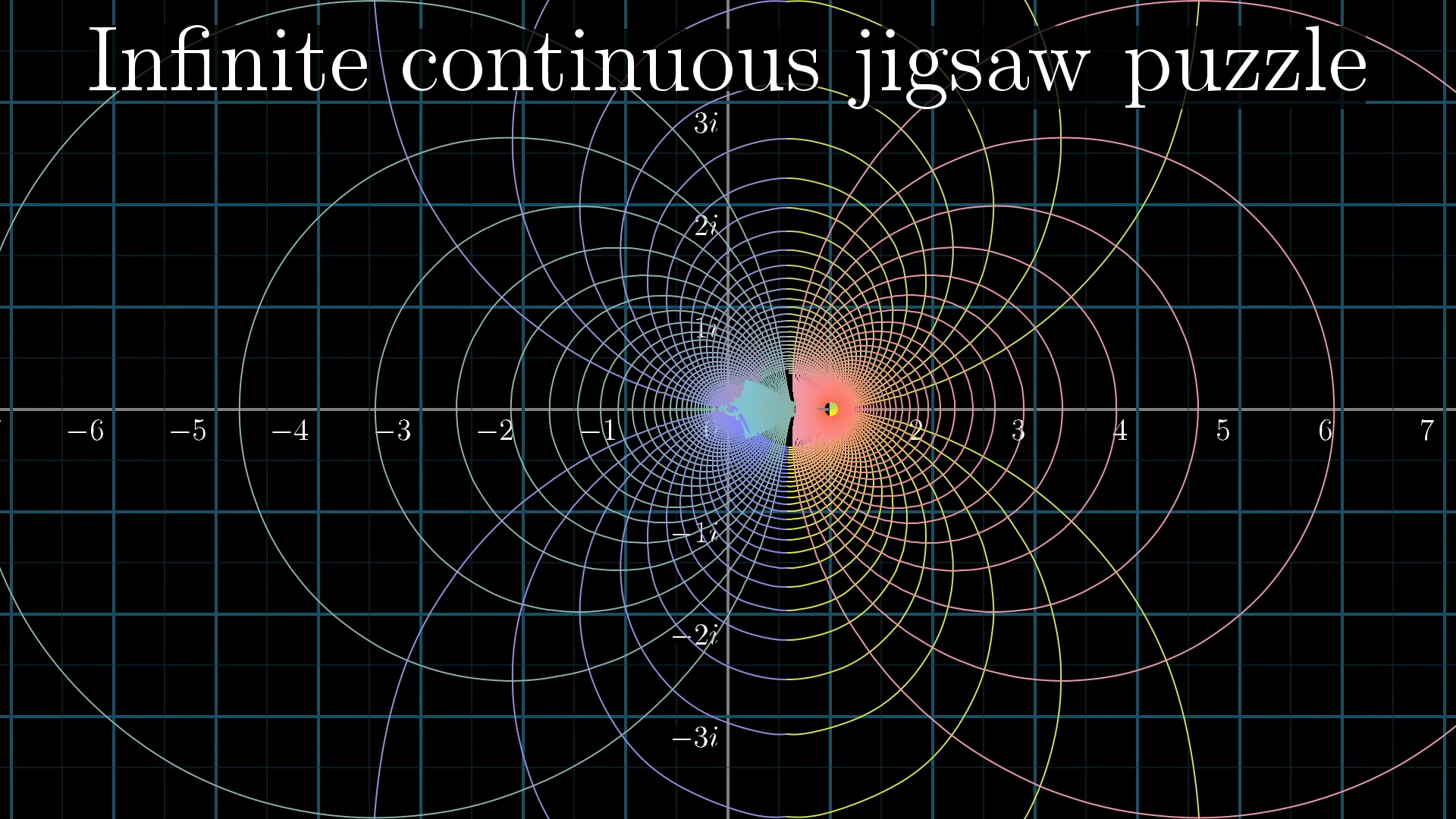

It’s kind of like an infinite continuous jigsaw puzzle, where the requirement of preserving angles like this locks you into one and only one choice for how to extend it. This process of extending an analytic function in the only way possible that’s still analytic is called, as you may have guessed, “analytic continuation”.

Recap

It's worth quickly summing up where we are. For values of s on the right half of the plane, where the real part of s is greater than one, plugging into converges, where a nice way to picture that sum is with a kind of spiral sum, since the imaginary part of the input causes a rotation in each term.

For the rest of the plane, we know that there exists one and only one way to extend this definition so that the function will still be analytic, that will preserve angles at every single point.

That’s a very implicit definition; it just says to use the solution of this jigsaw puzzle, which through more abstract derivations which I have not discussed we know must exist, but it doesn’t specify exactly how to solve it. Mathematicians have a pretty good grasp on what that extension looks like, but some important parts of it remain a mystery. A million dollar mystery, in fact.

The Riemann Hypothesis

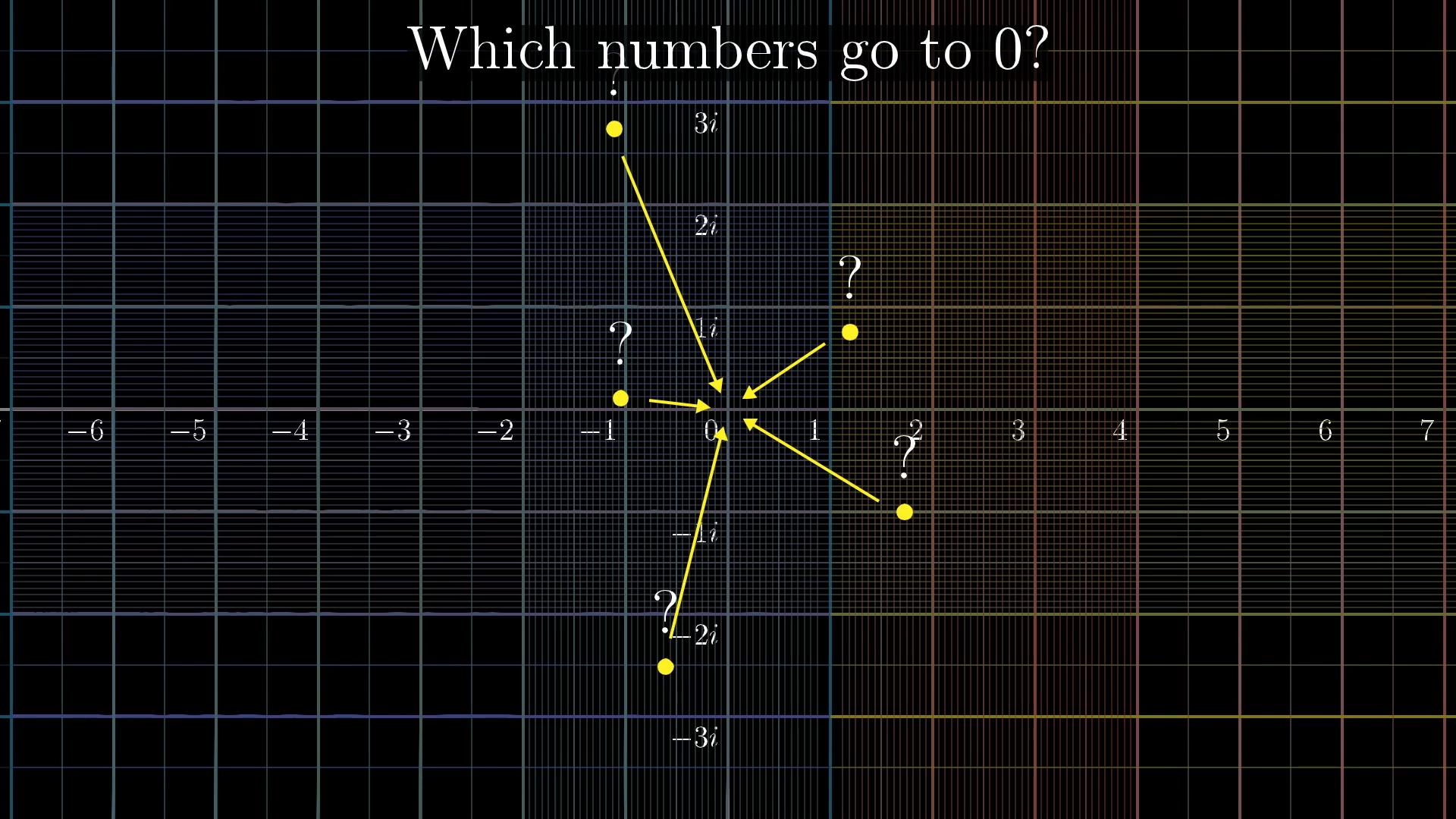

The places where this function equals zero are quite important. That is, which points get mapped onto the origin after the transformation.

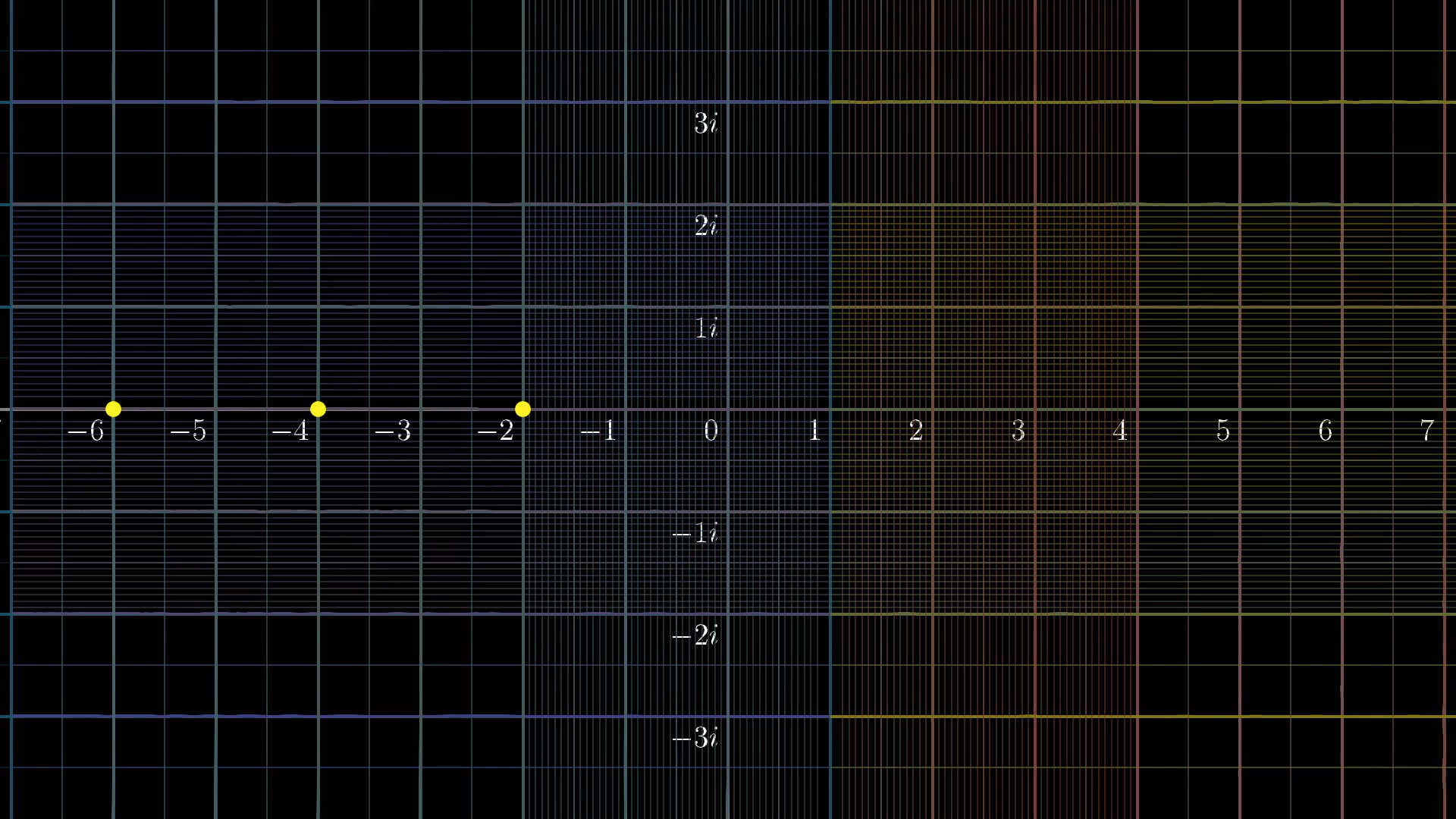

One thing we know about this extension is that negative even numbers get mapped to zero, and these are called the “trivial zeros” .

Here, we have -2, -4 and -6 on the number line prior to the transformation.

Notice how they all map onto 0

The naming here stems from the longstanding tradition of Mathematicians calling things trivial when they understand it quite well, even if it’s a fact which is not at all obvious from the outset.

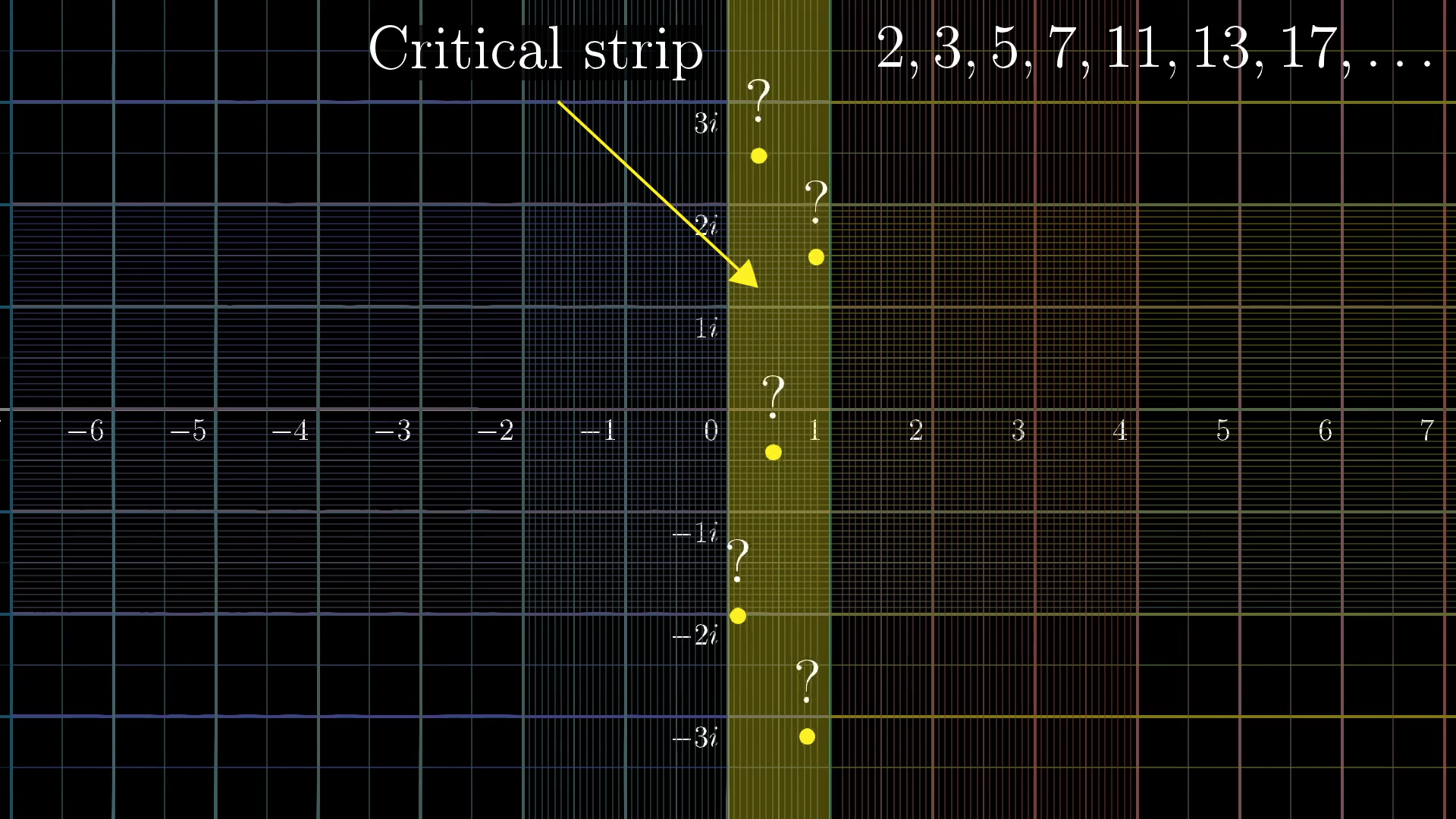

We also know that the rest of the points that get mapped to zero sit somewhere in this strip where the real part of sits between and , called the “critical strip”. The specific placement of those non-trivial zeros encodes a surprising amount of information about prime numbers.

Why this function carries so much information about primes is pretty interesting , and I might make a follow on video about that later, but for now, I’ll have to leave it unexplained.

Actually, we know quite a bit about those zeros. A mathematician will be able to look at the picture above and know that it's not right, since the first of these zeros sits around . Moreover, the zeros must be symmetrically placed around the line .

Riemann hypothesized that all the remaining zeros lie right in the middle of this strip, on the line of numbers whose real part is , known as the critical line.

If that’s true, it gives us a remarkably tight grasp on the pattern of prime numbers, and all the many other patterns in math that stem from this.

So far, when animating what the zeta function looks like, I’ve only shown what it does to the portion of the grid on the screen, which undersells some of its complexity. If I highlight this critical line and apply the transformation, it might not seem to cross the origin at all.

Here's the critical line, , before the transformation

Here's the critical line, , after the transformation

However, here’s what the transformed version of more of that line looks like... Notice how it passes through 0 multiple times.

A longer sample of the critical line after the transformation

If you can prove all non-trivial zeros lie on this line, the Clay Mathematics Institute gives you $1,000,000, and you’d also be proving hundreds if not thousands of modern math results that have been shown contingent on this hypothesis being true.

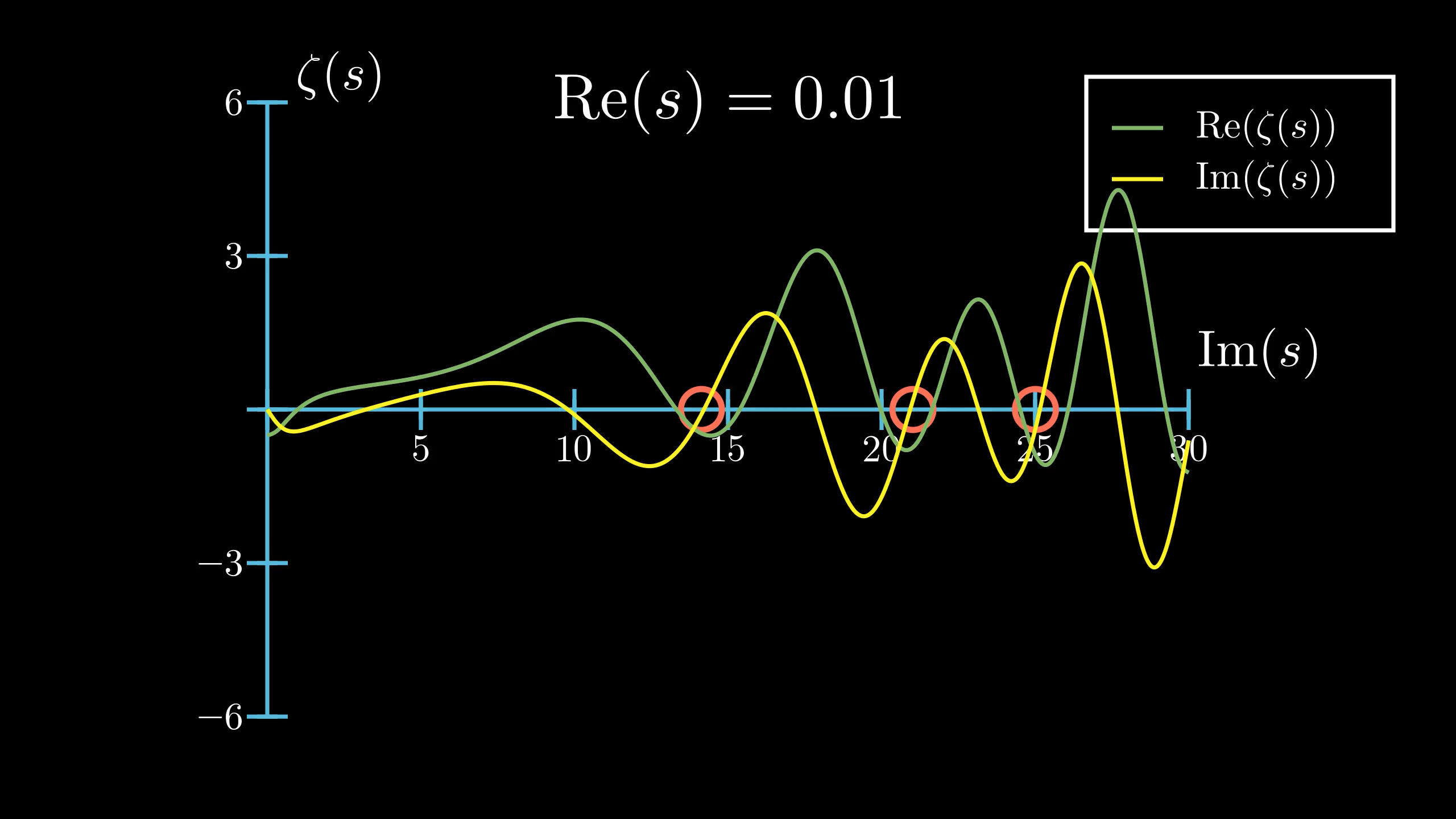

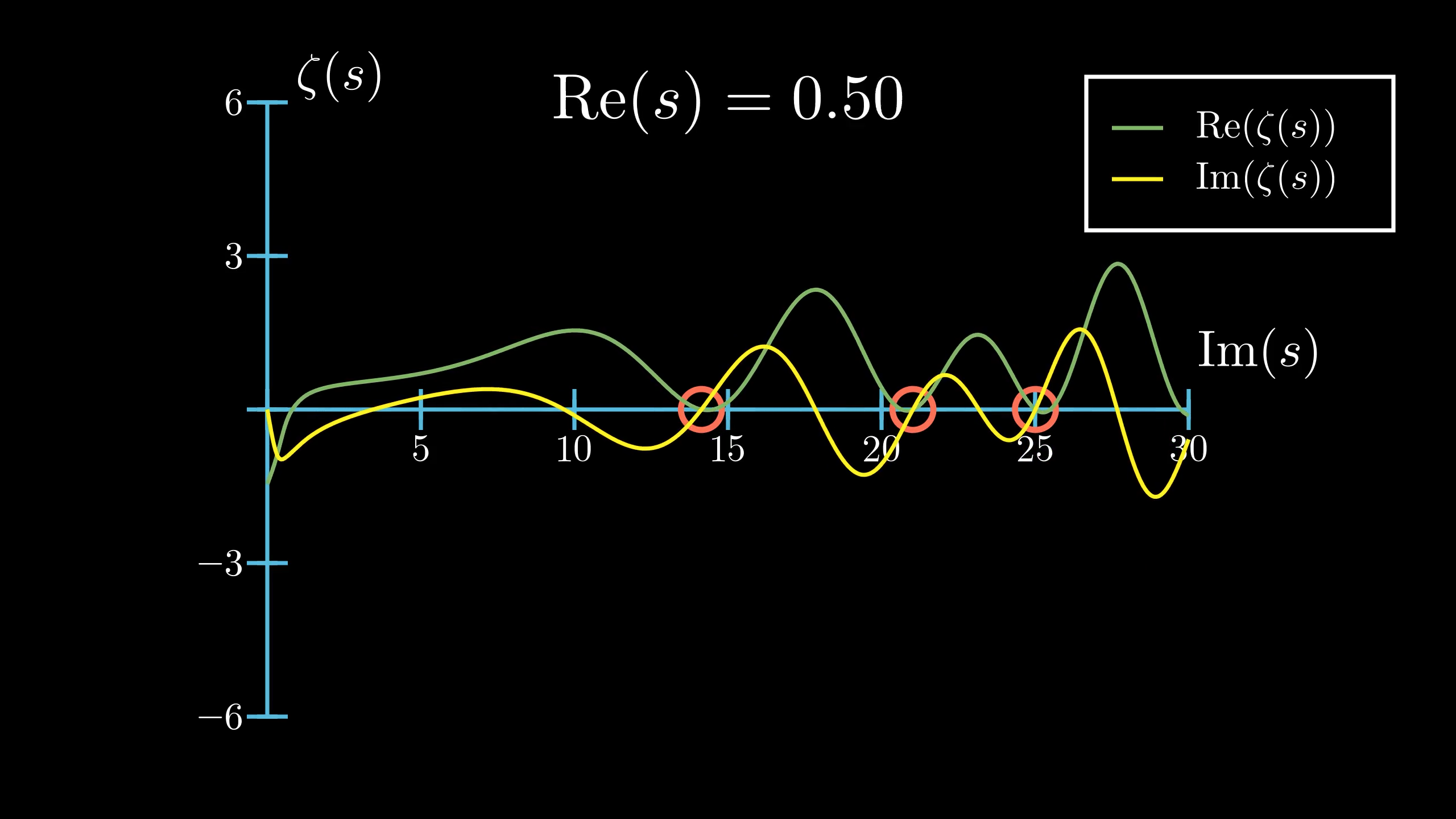

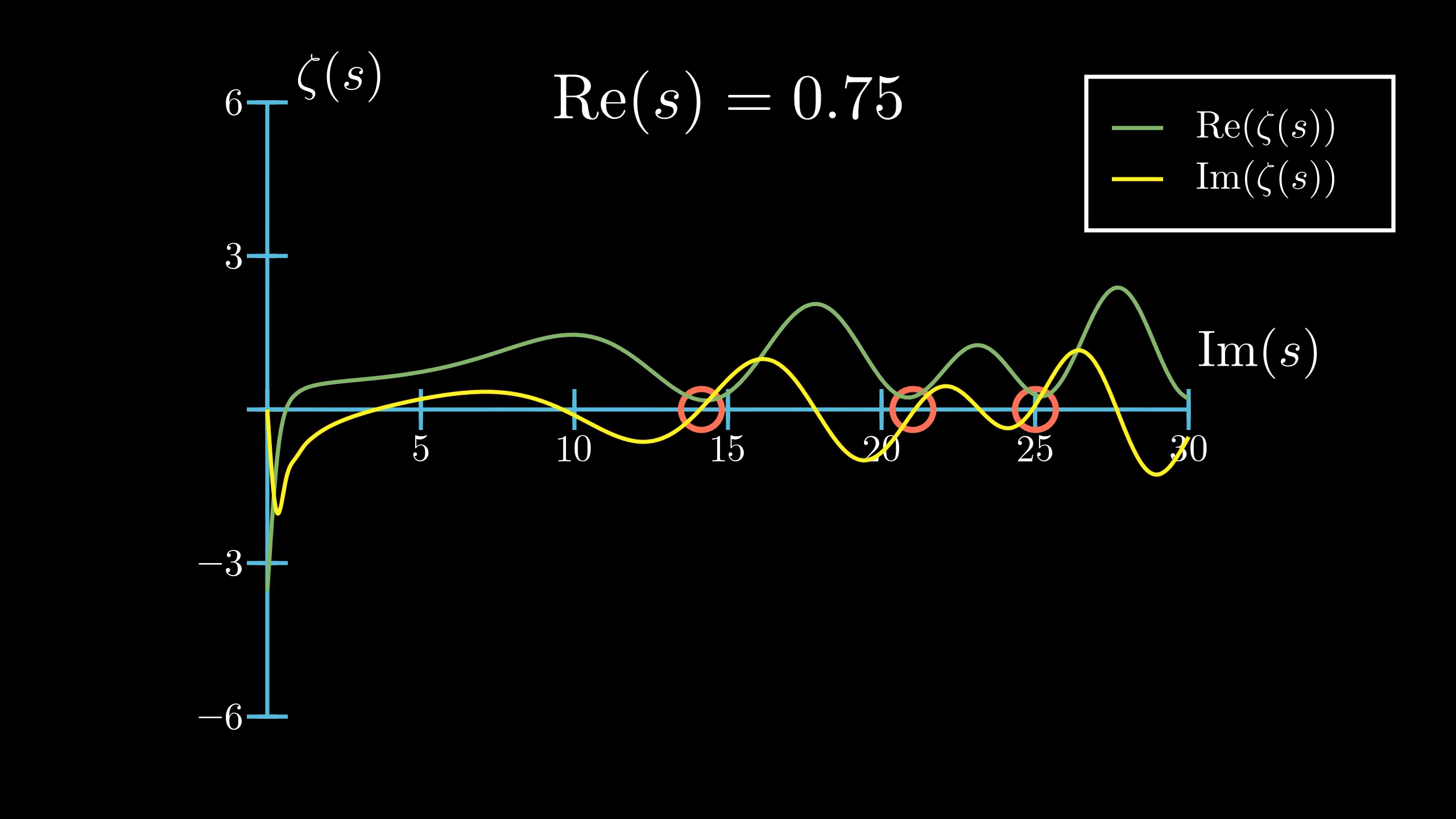

Here's another way to visualize the zeros of the zeta function. I've graphed the real component and the imaginary component of the zeta function on the -axis, and the -axis is the imaginary component of the input, . I've also highlighted the imaginary components of the first three zeros on the x axis in red.

Currently, the real component is . Watch what happens when I vary the real component from to .

Let's go back and stop at . Notice how the imaginary component and the real component equal at the red circles.

But if , the real and imaginary component do not equal at the same place.

What about this -1/12 business?

The next time you see the following sum floating around the internet, you now have the ability to understand what it's trying to say.

Specifically, one thing we know about the extended zeta function is that . This is a statement about the continuation of , not a direct fact about the sum . Remember, the definition of the zeta function on the left half of the plane is not defined directly from this sum! Instead it comes from analytically continuing this sum beyond the domain where it converges. That is, solving the jigsaw puzzle that began on the right-half of the plane where it more readily makes sense.

So is it okay to write that infinite divergent sum above? Perhaps not, since it runs the risk of misrepresenting very real math as producing nonsense. But then again, considering the uniqueness of this analytic continuation, the fact that the jigsaw puzzle has only one solution, it's very suggestive of some intrinsic connection between these extended values and the original sum.

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.